In Darkness, Through Cinema

From Zurich to Toronto, A Festival That Smelled Like Home

Majid Movaseghi – London |I began my professional journey in theatre, then moved into Iranian cinema as an assistant director. But it was a personal yearning for cinema that stirs thought—a kind of reflective, philosophical cinema—that pulled me deeper into a world of cinematic contemplation.

On one hand, years of theatre experience had grounded me in experimental approaches, especially the methods of Russian acting and directing theorists. On the other hand, the richness of Russian music, literature, and theatre—along with filmmakers like Dovzhenko, Grigori Kozintsev, Mikhail Kalatozov, Sergei Parajanov, Vadim Abdrashitov, Alexander Sokurov, Andrei Konchalovsky, Aleksei German, Nikita Mikhalkov, and Gleb Panfilov with his extraordinary film “The Theme”, compelled me to learn Russian.

The sheer desire to hear “The Seagull” by Chekhov in its original language led me to the very university where these filmmakers—and my own beloved Tarkovsky—had studied. A place once shaped by the teachings of Sergei Eisenstein, and later carried forward by his students: Mikhail Romm, Grigori Chukhrai, Marlen Khutsiev, and Sergei Gerasimov.

Encountering Tarkovsky’s films was a turning point. His work pulled me toward the aesthetic and theoretical dimensions of cinema, and that path eventually led to academic study in Moscow, and later, to teaching acting and directing at various universities.

In recent years, I’ve been fortunate to take part in major international festivals—as lecturer, filmmaker, critic, and jury member—across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. These journeys have taken me from the pyramids of Giza to the Great Wall of China, from the alleys of Venice to the temples of Dhaka, from the shores of Lake Zurich to the roar of Niagara Falls.

From Berlin’s bears to Tokyo’s kabuki, from Locarno’s leopards to Tbilisi’s clay jars, from the soil of my homeland to the palms of Cannes. Festivals like Visions du Réel, DOK Leipzig, and VideoEx—each focused on experimental, independent cinema—have shaped this path.

But contrary to popular assumptions about festivals as glamorous or leisurely affairs, my own experiences have mostly taken place in darkness—inside screening rooms, from early morning to midnight—watching, analyzing, and diving deep into each film’s layers of meaning. I sometimes wonder if that obsession was truly worth it.

Still, for me, cinema wasn’t just a profession; it was an aesthetic and intellectual necessity. These trips were never about beaches or photos. They were about silence, darkness, images, and questions. I see cinema through the eyes of a contemplative viewer—someone still looking, in every new frame, for a deeper understanding of the world and of self.

In 2015, not long after I had moved to Zurich, life felt like it had hit pause. Migration brings new memories, but also a strange stillness—especially for a filmmaker with a restless mind. In that period of seeking balance, I received an invitation from Pooyan Tabatabaei, the artistic director of the Eastern Breeze Festival in Toronto. It opened a new door.

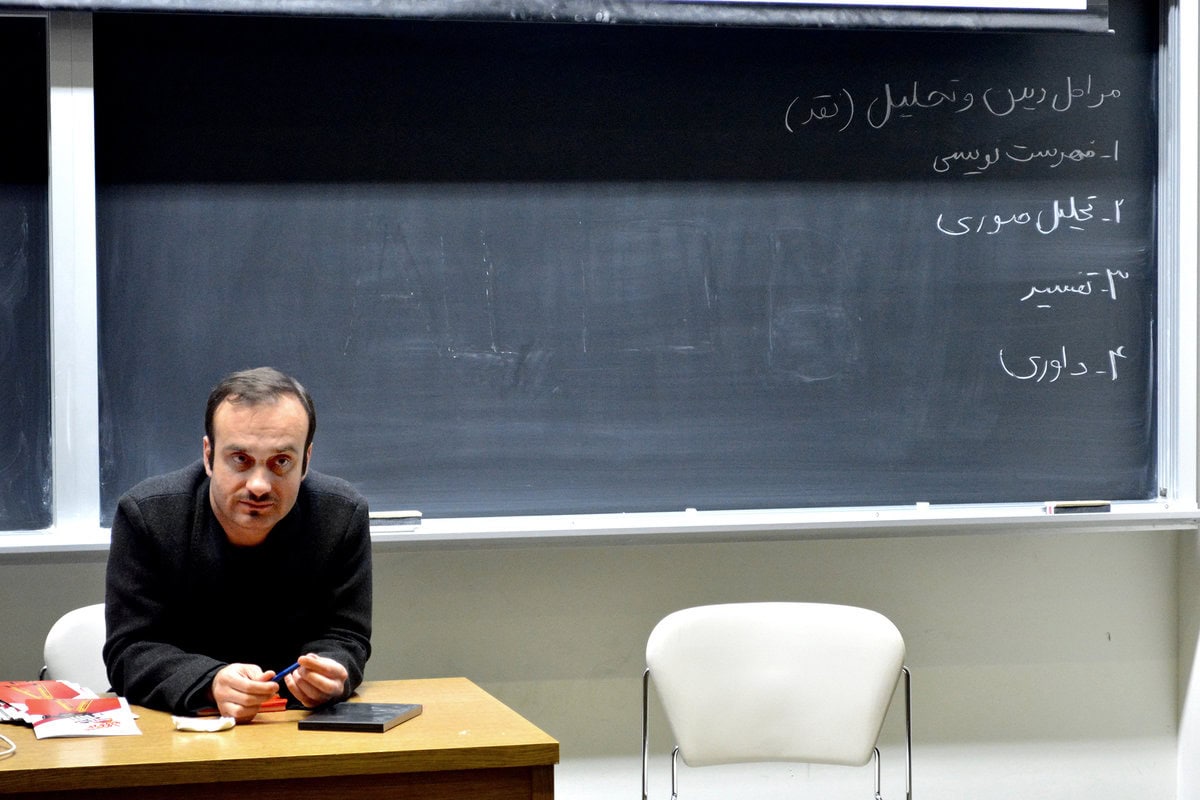

I had previously worked with the festival from inside Iran, serving on the selection committee the same year Hamid Jebeli was a workshop guest. The following year, I was invited to Toronto as a jury member and to lead two workshops—one on documentary cinema at the University of Toronto, and another on film analysis at Ryerson University. It was only my second international jury experience after Moscow, alongside several domestic and regional festivals.

Eastern Breeze (EBIFF) stood out for its focus on independent voices from the East, finding resonance in the heart of the West. Travelling from Zurich to Toronto with an Iranian passport was far from simple: visa hurdles, fingerprinting in Paris, endless paperwork. And yet, something in that invitation wouldn’t let me go—the thrill of watching films, of exchanging ideas, of feeling alive again through art. As Jean Cocteau once said, “Cinema is a dream we watch while awake.”

Toronto surprised me. A city that holds half the cultural memory of the Middle East in its bones—Persian restaurants, Farsi street signs, familiar faces with whom you could engage without translation, sometimes without even needing English. Everything smelled like home. From the bakeries to the corner diners in Persian neighbourhoods, everything echoed the past. One afternoon, while walking through “Tehranto” with Pooyan, I spotted a “Haida Sandwich shop”—it instantly took me back to my student days in Tehran.

During the festival, I conducted two masterclasses—one on the language of documentary cinema and the other on film interpretation—while also serving on the jury. But it wasn’t just another professional gig. It was something more intimate: a quiet reckoning with a part of myself. Judging films alongside peers from different cultures was a form of dialogue—an exercise in understanding the modern world through image and sound. It was an invitation to rethink, to feel the depth of storytelling, and to ask new questions.

On the festival’s sidelines, Pooyan and I took a trip to Niagara Falls. The roar of the water, amid the thawing Canadian winter, reminded me of the most moving moments in documentary cinema—raw, unfiltered, uninterrupted. He later gifted me one of his photographs from that day. It remains one of my most cherished memories. Returning to Zurich didn’t feel like a return. It felt like I had brought a piece of Toronto, its people, and its films, back with me. Eastern Breeze wasn’t just an event—it was a convergence of lived worlds, buried narratives, and identities still in formation.

Two years later, our collaboration peaked at the Dhaka International Film Festival in 2017. Pooyan, actor Levon Haftvan, and I were invited to judge and lead a “CineWorkshop” where, from concept to completion, seven short films were produced by an enthusiastic group of international students. Those days were unforgettable. Some of those participants went on to become successful directors and producers. Others stepped away from cinema altogether—perhaps, in a way, they were the lucky ones.

But Eastern Breeze didn’t just bring light. It also carried the bitter taste of parting. On my last night in Toronto, Levon Haftvan—so full of life and charm—hosted a dinner with his signature warmth and unforgettable cooking. Months later, not long after our time in Dhaka, he passed away—at the height of his artistic life. His voice, like the sound of Niagara Falls that day, still echoes in my mind.