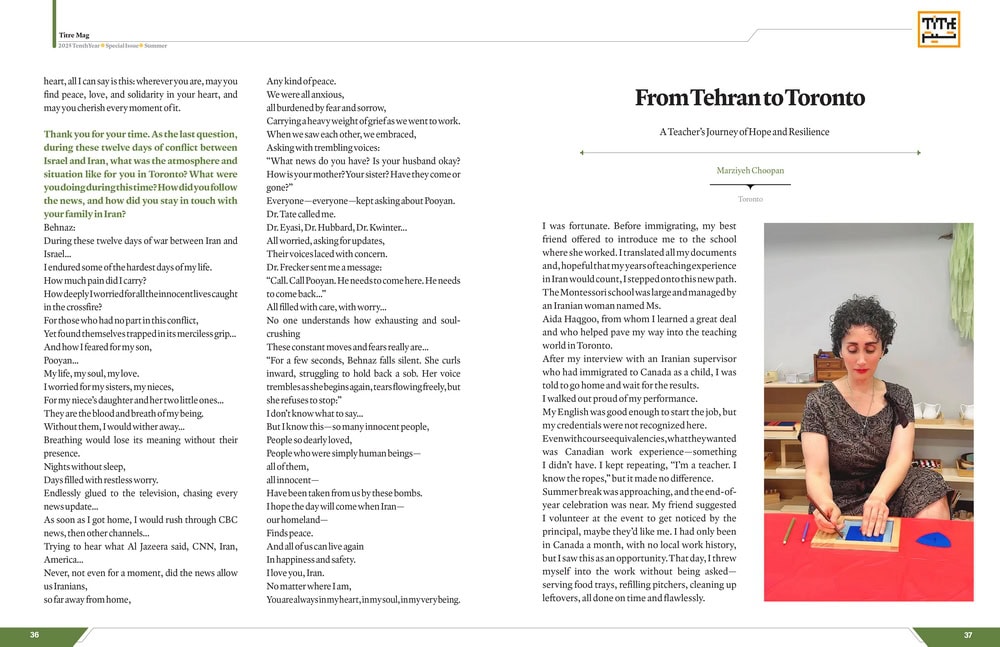

Marzieh Bahramchoobin – Toronto | I was fortunate. Before immigrating, my best friend offered to introduce me to the school where she worked. I translated all my documents and, hopeful that my years of teaching experience in Iran would count, I stepped onto this new path.

The Montessori school was large and managed by an Iranian woman named Ms. Aida Haghgoo, from whom I learned a great deal and who helped pave my way into the teaching world in Toronto. After my interview with an Iranian supervisor who had immigrated to Canada as a child, I was told to go home and wait for the results.

I walked out proud of my performance. My English was good enough to start the job, but my credentials were not recognized here. Even with course equivalencies, what they wanted was Canadian work experience—something I didn’t have. I kept repeating, “I’m a teacher. I know the ropes,” but it made no difference.

Summer break was approaching, and the end-of-year celebration was near. My friend suggested I volunteer at the event to get noticed by the principal, maybe they’d like me. I had only been in Canada a month, with no local work history, but I saw this as an opportunity. That day, I threw myself into the work without being asked—serving food trays, refilling pitchers, cleaning up leftovers, all done on time and flawlessly.

And at the end, my wish came true. The very next day, I started as a floating support staff and assistant in the after-school program. Cleaning restrooms, checking tissue and soap supplies, helping in the kitchen, distributing food and snacks—there was nothing I wouldn’t do. I put my master’s degree in my pocket and got to work. No time, money, or possibility to continue studying, but I had to gain experience.

My manager advised me to spend time in the school environment to understand its culture. What seemed simple was full of hidden nuances for someone coming from a very different system. How to speak, interact with children, communicate with parents, the line between affection and invading personal space, all was new and sometimes shocking. For example, just minutes after I hugged a child out of kindness, I was called to the principal’s office because the parents had complained. That incident sparked a shift in my perspective.

Following my manager’s advice, I enrolled in college. I received a government scholarship and took three years to earn my early childhood education diploma. Those years were my deepest learning experience, covering child psychology, nutrition, music, art, curriculum design, and working with children with special needs. Most importantly, I learned to see a child not as a helpless being but as an independent human on their own developmental journey.

Back in Iran, touching or kissing a child was a sign of love. Here, boundaries are clear. No photography, no giving snacks without permission, no touching; out of respect for cultural, religious, and personal differences. I truly understood what “diversity” means in practice.

Everything starts with the smallest details—like a classroom notice clearly stating which foods each child can’t have, without debate. Or the teacher’s professional dress code, no short skirts, low necklines, or sleeveless tops. Even passing the Montessori certification depends on adhering to such standards.

Gradually, I realized that friendship at work clashes with professionalism. My friendly behaviour sometimes got me into trouble. At first, I thought my culture was right, but experience taught me that working in Canada means following strict and serious rules. Any slip could mean losing certification or even fines. Here, the rights of students and parents come before the teacher’s.

One memorable experience was when I introduced yoga in class. I did simple morning stretches with the kids and asked parents to send mats. The next day, a complaint arrived—one parent claimed yoga conflicted with their religious beliefs. I initially resisted but soon understood that I must respect different beliefs and never judge absolutely. There’s no room for imposing views here.

Now, I have two new colleagues from Nepal, neighbours from Tibet. I consider this cultural diversity a gift of life in Toronto. The world has become both smaller and larger to me.

Getting to know people from different backgrounds, hearing their stories, and trying to understand and accept them is more than just an experience; it is life itself. Isn’t it?

This year, I prepared a folder about Iran for my class, from Talesh in the north to Khark in the south, from Baluchistan to Kurdistan. I selected dozens of photos and told them one by one how vast and rich our country is. I feel no one asks anymore, “Iran? Isn’t that Iraq?”

Because from within our classrooms, we proudly shout, “Iran.”

And this is how my immigration fatigue ends.

Brief Overview of Montessori Education: The Montessori school is an educational environment based on the philosophy of Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator. This approach emphasizes child independence, freedom to choose activities, experiential learning, and respect for the child’s natural developmental rhythm.

In Montessori classrooms:

- Children learn using specially designed materials at their own pace and according to their interests.

- The teacher acts as a guide rather than a lecturer or classroom manager.

- Mixed-age groups (e.g., ages 3 to 6) learn together to encourage peer learning.

- Focus is placed on order, concentration, independence, and problem-solving.

- The learning environment is calm, organized, and designed around freedom within limits.

The ultimate goal is to nurture independent, responsible children who are passionate about lifelong learning.