From Shadows to Spotlight

Celebrating Iranian Diaspora Through Art and Film

Parham Saleh, Arts & Culture Journalist – Toronto | It was a gentle spring afternoon when I met Pooyan Tabatabaei at a quiet café on College Street, not far from where, almost twenty years ago, he curated his first cultural event in Canada. The walls around us were covered in mismatched art. A few Persian prints hung beside faded vintage posters. I told him it reminded me of the early flyers for Six Weeks of Iranian Art. He smiled gently. “Back then, we had no big budget. Just our gears, a few friends, and a big idea.”

That idea became one of the most meaningful and community-rooted cultural series Canada had seen. It began as Six Weeks of Iranian Art, and later evolved into the Eastern Breeze International Film Festival. Together, they reshaped the artistic voice of the Iranian diaspora in Toronto. They introduced Middle Eastern cinema to new audiences and offered a deeply human counter-narrative to the region’s mainstream portrayals.

The birth of the movement it sparked, Pooyan told me, was lit during a visit to the Toronto studio of his friend, Mahmoud Meraji, a celebrated Iranian painter. “We were just sitting there, surrounded by his paintings,” he said, “talking about how fragmented our presence was here. Persian events existed, but they were small, scattered, nearly invisible to Canadian audiences. We wanted one serious event–bold and unified–to showcase the richness of Iranian contemporary art. Artists were mostly showing work within our own circle, not to the wider public.”

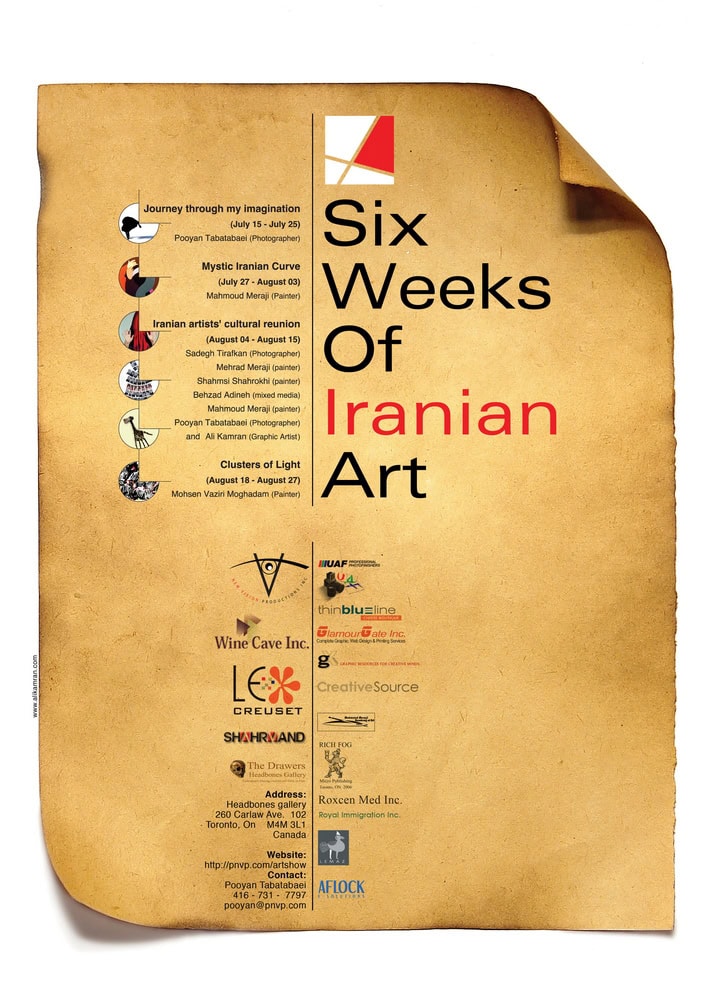

That conversation laid the groundwork for what became the Six Weeks of Iranian Art festival, launched in 2006. Pooyan served as the curator and lead organizer, overseeing every part of the programming, from exhibitions to performances to outreach. The first edition was modest in scale, but it held remarkable ambition and spirit. It showcased Iranian artists based in Canada, placing modern and contemporary aesthetics at the forefront.

The entire festival run lasted six weeks, and each exhibition was presented in a ten-day rotation, allowing artists to have their own space and time to engage with the audience. It opened with a photography exhibition by Pooyan himself. Not long after, Mahmoud Meraji filled the gallery with a deeply expressive collection of his paintings. Then came a historic exhibition of works by Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, a pioneering figure in Iranian modern art, whose paintings and sculptures were being exhibited in Canada for the first time. This show carried an emotional weight, marking a cultural milestone.

In the group exhibition, a range of powerful visual voices were brought together. One of the highlights was a series by the late Sadegh Tirafkan, whose work on identity and memory resonated across generations. Traditional music performances brought another dimension to the festival, most notably through a spellbinding set by tar virtuoso Araz Salek.

Throughout the run, the space evolved into more than just a gallery. It became a living, breathing studio. “As the curator,” Pooyan said, “I asked every artist who had a solo show to create at least one new piece during their ten days in the space. It created a beautiful interaction between the artist and the audience.”

He smiled as he remembered, “Mahmoud created a massive painting, nearly three meters wide. It was bold and breathtaking. And Mohsen started reshaping one of his sculptures right there in the gallery. It was alive.”

The visual identity of the festival was shaped by celebrated Iranian graphic designer Ali Kamran. His poster design became iconic within the community, combining cultural familiarity with sharp, modern sensibilities.

The event drew attention quickly. Pooyan was invited to speak on Canadian television. The festival was covered in mainstream news. A letter of support arrived from Prime Minister Stephen Harper. The Mayor of Toronto paid a visit. Several local and federal politicians visited the exhibitions to see them firsthand. “If it wasn’t the very first Persian art event in Canada to receive that kind of coverage, it was one of the first,” Pooyan said.

The venue was Headbones Gallery, run by the Canadian artist and critic Julie Oakes. Surrounded by artist studios, it became a hub of social and intellectual activity. Each afternoon, the backyard would fill with artists like Gord Smith, Scott Ellis, Srdjan Segan, Irina Dascalu, and Ashley Johnson. “We’d share food, drinks, stories, and laughs,” Pooyan recalled. “It wasn’t just a festival. It was a conversation.”

Then Pooyan’s phone rang. It was Mahmoud Meraji.

“Can I ask him a question?” I asked politely.

Pooyan nodded and put his phone on speaker.

I introduced myself and asked, “After all these years, what stands out in your memory about the festival?”

There was a warm pause, then laughter.

“It’s not easy to sum it all up, especially on a phone call, but let me tell you what I do remember.”

His voice became tender.

“The first thing that comes to mind is meeting Master Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam, a pioneer of modern art in Iran. I was with Pooyan Tabatabaei that day. What stays with me most clearly—and still makes me smile—is a morning walk with Vaziri along Carla Street. It was a bright, sunny morning. We were walking together when we ran into Gord Smith, one of Canada’s most brilliant sculptors. A conversation started between them about Vaziri’s sand-based artworks. Vaziri said, ‘I created those works before Jasper Johns ever touched the idea.’

And Gordon Smith, with kindness and respect, replied:

‘It doesn’t matter to me who did it first, you or Jasper Johns. What matters is the power of the work itself. And your work? It speaks. It holds its own. That’s what really matters.’

That moment–his words–stayed with me. And I remember Pooyan was right there. It left a mark on both of us.”

Mahmoud continued, “Another unforgettable memory is the day my son, Mehrad, drew a live portrait of Vaziri Moghaddam. I had a class that day and couldn’t be there from the beginning. But when I arrived at the venue, I saw Vaziri seated across from Mehrad, who was sketching him with charcoal. The result was remarkable, deeply expressive and full of life. That moment belongs to the first edition of the festival, and it remains one of the most memorable for me.”

“In the second edition, my role was more limited, but I was still involved. That year, they had also added an Iranian film festival alongside the visual arts program. A number of guests were invited from Iran, including Mr. Hamid Jebeli and his wife. I had really hoped to meet them, but unfortunately, I missed the opportunity. I still regret that.”

“There was also one of my former students, Ms. Rajayi, who by then was in her early 80s. She had only recently taken up painting, just a few years earlier, with me. Her work showed astonishing sensitivity and detail. She participated in the festival with tremendous care and clarity. Her pieces deeply moved both me and my friends. May her soul rest in peace.”

He laughed gently again.

“Pooyan, I’m not sure I greeted you properly at the start. Hello again, my friend.”

Then he added with a playful tone, “Make sure the memories I shared are correct.”

We all laughed. A brief call became a window into a time full of warmth and art.

Our pastries had arrived. Pooyan glanced at his phone, then put it away. We kept talking.

Expanding the Vision: The Second Edition and Beyond

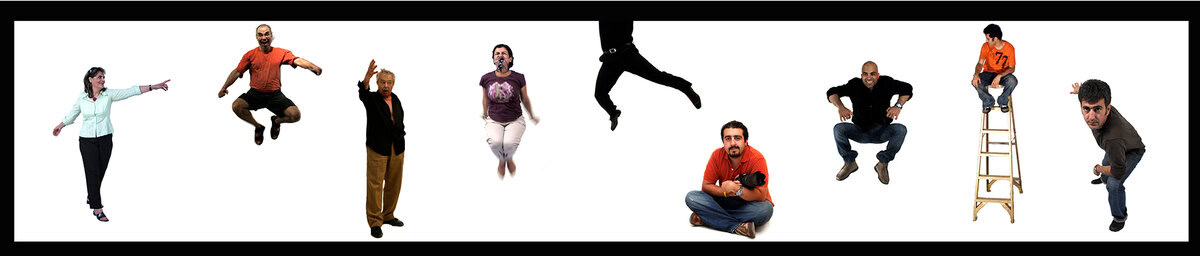

The second edition of the festival was even more ambitious in scope. Buoyed by the success of its first year, the team expanded, the vision broadened, and the festival gained new energy. “We expanded our team of promoters and brought in fresh voices,” Pooyan explained. “We added Levon Haftvan to oversee theatre and literature. Sasan Asvandi, Farhad Ahi, and Keyhan Mortazavi joined our cinema section. Julie Oakes and Mohsen Vaziri became key figures in the visual arts department.”

Yet, not everything went smoothly. Just ten days before the opening, after Pooyan had returned from Iran with the artworks for the Iranian section, he discovered that the new gallery space they had planned to use was not ready. “The gallery owner never informed us,” he said with a hint of frustration. “We were stuck with a smaller venue. It was too late to find another place. But as the saying goes, the show must go on.”

Despite that setback and the gallery owner’s neglect, the festival opened to great acclaim. This time, the event took place across two major venues in Toronto and featured over 150 artists spanning the visual arts, literature, and cinema. Thousands attended, eager to engage with the rich diversity of Iranian and Middle Eastern creative expression.

The theme that year, “The Art of the Moment, the Moment of the Art” explored how art reflects identity, time, and diaspora experience. Alongside exhibitions and performances, six creative workshops offered visitors a chance to learn and connect. The cinema section thrived, drawing Canadian audiences to films from across the Middle East and North Africa.

Once again, the media took notice, and the opening ceremony was graced by the Premier of Ontario. Shelley Carroll, then Budget Chief Councillor, praised the festival as a national model for diaspora-led cultural engagement. The festival was no longer just a community event; it had become a movement. As the sun warmed the outdoor patio where we had moved for some fresh air, Pooyan took a quick phone call, then returned with a smile. We continued our conversation, flowing naturally into the evolution of the festival.

From Gallery Walls to Silver Screens: The Birth of Eastern Breeze

By 2013, the landscape of Iranian and Middle Eastern art in Toronto had evolved. Iranian cinema was gaining global recognition, and audiences hungered for more nuanced storytelling from the region’s voices. It was the natural moment for Pooyan to launch the Eastern Breeze International Film Festival, a festival dedicated specifically to showcasing short and mid-length films from the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia, united by what Pooyan calls “an eastern taste or philosophy.”

The first edition of Eastern Breeze was modest but crafted with care and intention. By the second year, it had blossomed into a vibrant showcase of over 80 films from 35 countries. The selection was broad yet cohesive, featuring Iranian animated shorts, documentaries from Afghanistan, experimental films from Lebanon, and India. One film that left a lasting impression was Red Line, an Iranian animated short by Mona Abdollah Shahi, which used allegory to explore the futility of war. Pooyan recalled, “After the film ended, the audience sat in silence for a full minute. It was deeply moving.”

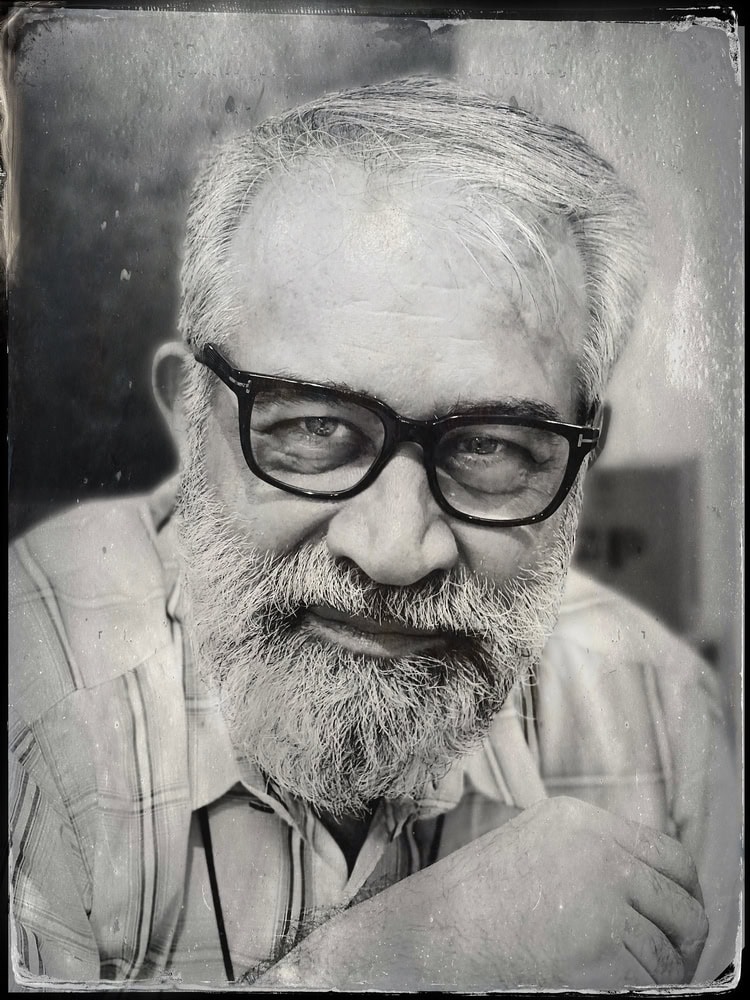

That year also saw the presence of renowned Iranian filmmaker and actor Hamid Jebeli, who served on the jury and presented three of his films in person. Pooyan smiled at the memory. “We weren’t sure we could afford to bring him, but we made it happen. Hamid is a true artist. Travelling outside Iran is rare for him—he has only attended a handful of festivals abroad in his life. I was honored he accepted the invitation and stayed with me in Toronto.”

Hamid’s wife, Zohreh Behbahani, accompanied him, and together they spent forty-five memorable days immersed in the festival. The community around the festival was tight-knit—Kayhan Mortazavi, a well-known Iranian set designer, had known Hamid for years. Sasan Asvandi, the sound engineer, had also worked briefly with him. Soheil Parsa, the celebrated Iranian-Canadian theater director and a longtime friend of Hamid, joined the festivities. The connection between these artists filled the festival with energy and camaraderie.

Hamid ran a workshop titled “Filmmaking with What You Have,” which became an unexpected highlight. Each day, a member of the festival team would join to assist him, helping participants dive deeply into the craft. Alongside this, Pooyan curated a joint photography exhibition with Hamid called Beyond Frames, which also garnered praise.

Before wrapping up, Pooyan shared a special story about a commemorative event in Montreal. The Iranian association at McGill University had arranged a celebration of Hamid’s career. Film producer and educator Saeed Armand joined Pooyan and Hamid on stage to honor his work, marking a moving night that underscored the festival’s growing influence.

Later on, I managed to contact Mr. Saeed Armand for his thoughts on the festival. Though deeply occupied and busy, he generously took the time to send me the following note a few days later. His words were both surprising and deeply touching:

“A few days ago, our home in Toronto was completely consumed by fire. Fortunately, no one was inside at the time, and thankfully no one was harmed, but everything we had built together was lost in flames. During these challenging days, the kindness and support of friends and family have been a lifeline.

Still, every time I gaze at the ashes of our former home, a flood of memories and treasured moments from all those years rush through my mind like a vivid movie playing over and over. Amidst all those images, one face stands out brighter than any other: Pooyan Tabatabaei.

I have known Pooyan for many years. He is the kind of person whose presence fills a room even when he is not there. He speaks with warmth and energy, his voice unforgettable, and carries a joyful spirit that naturally spreads happiness to those around him.

Pooyan is relentless in his passion and work ethic, a force of nature impossible to ignore.

Over the years, I have visited countless festivals and galleries across the globe, yet few artistic experiences have left as deep an impression as the Eastern Breeze Film Festival and the Six Weeks of Iranian Art project, both passionately created and led by Pooyan.

The memories of those times are so rich and abundant that sharing them all would take hours. It was a space filled with genuine warmth and camaraderie yet marked by professionalism and creative energy, buzzing with art, innovation, and moments that demanded your full attention.

I deeply wish Pooyan endless success in all his future endeavors. Whenever his name is involved, you know something meaningful, alive, and full of promise is about to happen, and you know you must be there. He is not just a true artist but also an exceptional human being. And that says everything.”

We had been talking for nearly two hours, the conversation flowing easily yet deeply. Suddenly, Pooyan’s timer rang softly on his phone. I realized then that this must have been the full time he had set aside for our interview. He reached over and turned it off.

I quickly apologized. “I’m sorry if I took up too much of your time. If you’re pressed, we can pause here and continue another day.”

He smiled warmly, shaking his head. “No, no. There’s not much left. Just one more festival to talk about and then we’re done. If you want, we can wrap it up now.”

Relieved, I nodded and prepared to dive into the final chapter of this remarkable story.

The Final Chapter: Saying Goodbye to the Visual Arts

Pooyan’s tone softened as he spoke of the last series of festivals. “It was heartbreaking to say goodbye to the visual arts section. That part of the festival was close to my heart. But based on what I’d seen from the younger generation of Iranian artists, I felt we had already given them a strong foundation. Also, the budget was tightening. Private sector sponsors were becoming scarce.”

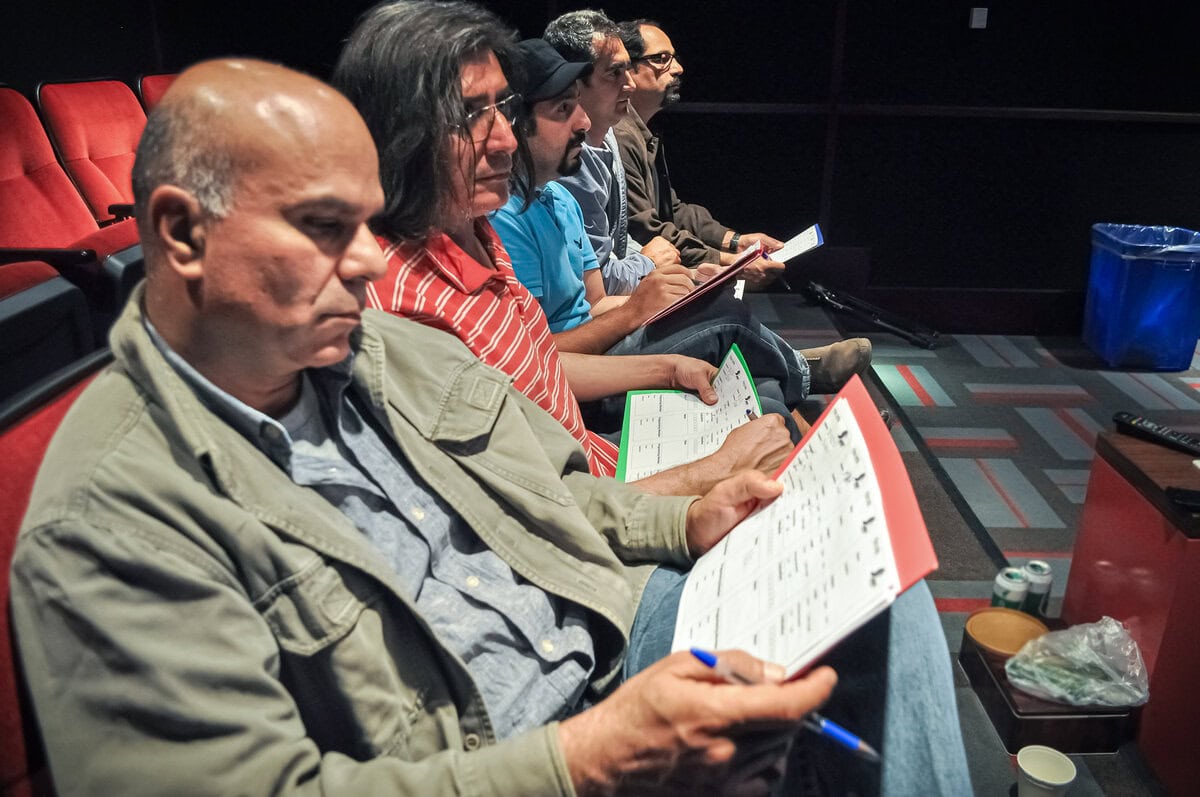

With those realities, the festival shifted its focus fully to film. The selection committee remained much the same: Kayhan Mortazavi, Farhad Ahi, Sasan Asvandi, Mostafa Azizi, and Pooyan himself. The jury was composed of three artists. That year, they received a large collection of films and managed a five-day festival.

One special guest was Majid Movasseghi, an Iranian filmmaker and critic from Switzerland. He served on the jury panel and led two workshops—one at Ryerson University and another at the University of Toronto. The workshops were highly praised and added a rich educational layer to the festival.

Pooyan smiled thoughtfully. “Strangely, I don’t remember many details about that festival. But Majid might be able to add more.” He glanced at his phone and shared Majid’s contact. I reached out, and a few days later we spoke over video chat. Majid said:

“This trip had something very special for me. It was actually my first time travelling such a long distance — to a place like Canada — for a film festival. I was in my early thirties back then, maybe thirty-four or thirty-five. Of course, I’d already had some experience presenting work, but Eastern Breeze was different.

It felt like a unique mixture; a blend of my homeland and something entirely new. There were so many Iranians in attendance that I was hearing Persian everywhere again, but at the same time, there were all these different cultural layers coming together. It was vibrant. It was alive. Photography, poetry, music, all these elements folding into one another.

And I think that had a lot to do with the fact that Pooyan, as the festival director, is also such a skilled and intuitive photographer. His vision gave the whole festival a strong visual character. For someone like me, who’s always seen image and visual rhythm as core to cinema, that meant a lot. Everything complemented everything else, each part of the festival enriched another.

I remember the workshop I gave. I opened it with images by Henri Cartier-Bresson. That choice wasn’t random. Later, I found out that Pooyan had been mentored by people at Magnum. That really stayed with me, and it explained a lot about his curatorial eye. There were constant moments of discovery like that throughout the festival.

I was also part of the jury, alongside Mostafa Kherghepoosh and a German woman filmmaker, unfortunately her name escapes me now, but I remember how thoughtful her comments were. The selection process was careful, engaged. We screened some strong films.

There was one in particular, from Israel, that really stood out. It took a bold, critical look at the way people are surveilled; how women sit behind screens and watch others from a distance, like puppets under a drone’s lens. You saw people moving, getting shot, being tracked. It was a film about control, power, and distance. Even now, that film still has something urgent to say. I believe it ended up winning the top prize, and it deserved it.

One part I really valued was giving masterclasses at Ryerson, and one at University of Toronto. In any case, it was a prestigious academic space, and the participants were thoughtful and serious. I had strong conversations there, the kind that stay with you.

There was also a beautiful rhythm running through the whole festival, a rhythm created by the mix of voices. Siavash Shabanpour brought poetry into the space. Pooyan, brought photography. Others added music. It was as though the festival itself was building a kind of collective, improvised composition, a music of its own. And language, Persian, played such an important role. It created a kind of unity among people who otherwise might have felt far from one another.

I must mention one night that really stuck with me, the after-party, right after the closing ceremony. I walked into this packed club, the music was loud, people were dancing, and then gradually I started to notice nearly everyone there was Iranian. It was funny and surreal, I had this moment where it hit me, Oh wow, there really is a huge Iranian community here in Toronto. That realization landed hard.

But what made this whole experience truly unforgettable was something deeper, the human details. Pooyan, even though he was the director of the whole event, he came to the airport to pick me up. That stayed with me. It created an instant sense of ease, of calm. And that atmosphere, that kindness, stayed throughout the festival.

And of course, I’ll never forget that photo of the three of us: Pooyan, me, and Levon Haftvan. That image holds a lot. Levon had such presence. That moment, and that photo, will always stay with me. May he be remembered with peace.”

Why did you stop the festivals?

Before we left, I asked the final question: Why did you stop the festivals?

Pooyan lifted his head and fell silent for nearly a minute, his gaze drifting toward the open sky above us. A subtle, almost secret smile crossed his lips. Then he looked back at me and said softly:

“For every decision, you have to weigh many factors. By the time the festival was growing, and we needed to scale up, it required a large budget and a big team to handle all the work. On top of that, many members of our core team were becoming occupied with their own projects. Meanwhile, the Iranian government began funding a week-long film screening event, which they called a festival. It might sound laughable, but the truth is, they had the money and the films. This caused private sector funding to shift in their direction.

At the same time, a new generation of Iranian immigrants arrived in Canada. Many were connected to the Ahmadinejad era, either new money or individuals closely tied to the Iranian government. Running an independent film festival became increasingly difficult. It felt like fighting a quiet, invisible battle against many newcomers. So, we decided to put the festival on hold and see what the future would bring.

2012 | during the Six Weeks of Iranian Art Festival

That said, we continued to screen selections of our festival winners at the Royal Ontario Museum during their events. For nearly two years, we held weekly screenings of Iranian films in another cinema. So, we didn’t stop completely, we just paused the official festival. Some of the challenges we faced are invisible and difficult to speak about openly. We were simply a group of artists wanting to promote and celebrate art. We weren’t bankers chasing fortune or fame seekers. We lived art, created art, and celebrated art.”

As a journalist who has covered many cultural events, I can say with certainty that few festivals combine the artistic vision, emotional depth, and political relevance that Eastern Breeze did. Its importance went far beyond film screenings. In a city like Toronto—diverse, multicultural, and still learning how to listen—Eastern Breeze filled a vital gap. It brought stories that mainstream channels often overlook.

“I always say,” Pooyan told me, “Our films don’t ask for sympathy. They offer insight. They invite Canadians into our living rooms, our kitchens, our memories. That changes everything.”

He also mentioned, “Let’s not forget the Diaspora Film Festival, run by my dear friend Shahram Tabe here in Toronto. That festival is older than ours and does a remarkable job. I was fortunate to be in Toronto for this year’s event and saw some incredible films. Despite the many challenges independent festivals face—especially with topics like ours and his—Shahram keeps going strong and continues to address important gaps.”

The strength of the Eastern Breeze International Film Festival came from its ethnic specificity, something many large festivals shy away from. But for Pooyan and his team, that was never a limitation; it was an invitation.

“By focusing on Iranian, Middle Eastern, and North African voices, we don’t exclude others—we invite them into our world.”

For Farsi-speaking Canadians, both Six Weeks and Eastern Breeze were more than festivals, they became cultural lifelines. As one attendee told me, “It felt like seeing my childhood on screen, in public, without shame.”

Closing my notebook, we stood to leave. I asked Pooyan what keeps him going. He paused, his eyes softening as he looked out into the fading light. “I believe in tenderness,” he said quietly. “Our people have been through so much. And yet, we make art. We write poems. We make films. That is resilience. And that deserves to be seen.”

That is exactly what Six Weeks of Iranian Art and the Eastern Breeze International Film Festival achieved: shining a bright, beautiful light on stories that would otherwise remain in the shadows. In doing so, they redefined Iranian representation in Canada and set a new standard for building bridges between cultures through art.