To the Promised Land

A Reportage on Jerusalem International Film Festival

Massimo Lechi

Italy

Film Critic based in Italy

After decades of denial and indifference, during this apparently never-ending phase of economic crisis, Europe has started realizing the actual existence of refugees. All of a sudden, what was once sealed within the African or Middle-Eastern natural borders – thousands of people in need trying to run away from war zones, famines and religious persecutions – has reached the Mediterranean coasts. Out of the blue, migrants’ faces appeared on television and in magazines, pushing into the spotlight stories of violence and deprivation. In our turmoil-ridden time, the concepts of hope, loss and displacement have unexpectedly returned to be relevant in public debate. And in many cases this slow process of recognition has gone even further: migration is not only a temporary political and humanitarian tragedy, but also something deeply rooted in our history, one of the pillars on which the Western World was built.

Since almost every Israeli story is also a story of immigration – or of return, from a Jewish perspective – it’s not surprising at all that several documentaries openly addressing the above-mentioned subjects premiered to positive reviews at the 33rd edition of the Jerusalem International Film Festival. The programming team headed by Festival director Noa Regev – who runs both Israel’s biggest cinematic event and the local Cinemateque with the support of the Jerusalem Foundation – managed to shape a rather interesting Israeli documentaries’ section, with movies focusing on social and historical issues. Some of them ran directly through the lives of men and women who once struggled to find a place in the coveted Eretz-Israel, allowing the audience to discover hidden parts of the country’s past.

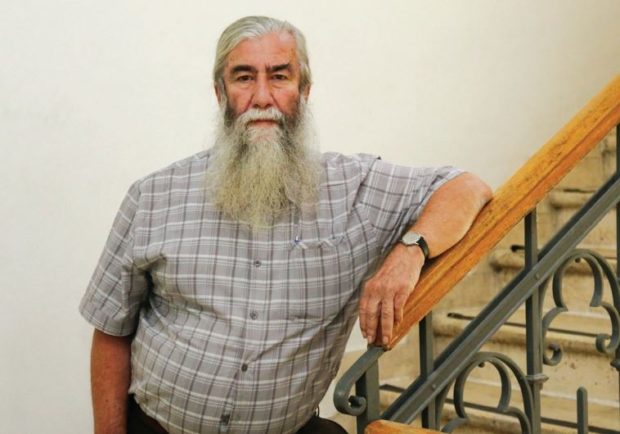

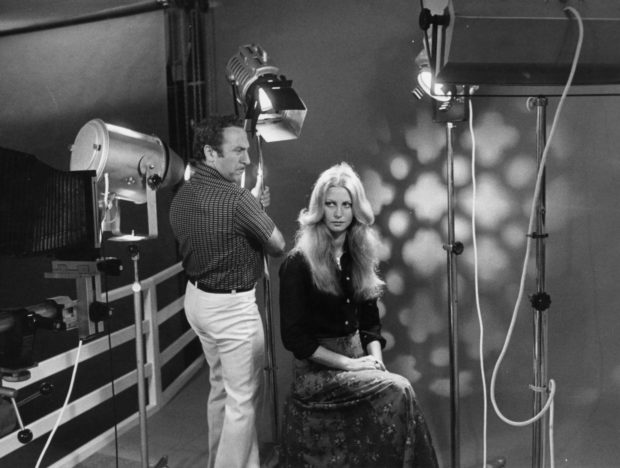

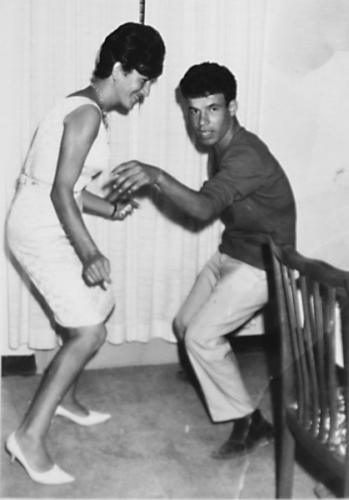

Michael Alalu’s Pepe’s Last Battle, Kobi Farag’s Photo Farag and Michal Aviad’s Dimona Twist, in particular, received warm reactions, with the latter also winning the Van Leer Award, the category’s top prize. Though quite different from one another in terms of structure, ambition and even quality, they all deal with stories of Jews who left their birthplaces and came to Israel after 1948, in search of a better life.

It could sound inappropriate to compare who, back in the Forties, Fifties or Sixties, immigrated to Israel under the Law of Return to today’s asylum-seekers. Running away from hunger and poverty is not the same as returning where the Prophets lived, many would say. Or is it? A closer look at the biographies of these three movies’ protagonists might in fact suggest the opposite. For many Israelis, in retrospect, Aliyah proved to be the only alternative to exile.

Pepe Alalu, for example, adventurously left Peru in the Sixties, in order to follow the Zionist dream. He literally came to the Middle East out of idealism, without being able to speak a word of Hebrew. A well-known figure in Israeli politics, having been a member of Jerusalem’s city council for countless terms, he doesn’t seem to have changed much over the years: he is still the same passionate South American leftist fighting the Right and the ultra-Orthodoxes, with a ponytail and an exotic accent. His son Michael films him during his unsuccessful campaign as mayoral candidate (the title’s last battle) with respect, delivering few moments of tenderness and laughter. What would have Pepe become if he had stayed in Peru? Maybe a greedy bourgeois, or more likely, as the old man puts it with ironic self-indulgence, a suicidal guerrilla. And what would have happened to his Jewish identity?

As for Farag Peri, the enigmatic character chased on screen by his nephew Kobi in a heartfelt yet unfinished attempt to investigate the downfall of a glorious Mizrahi family, he reached Israel in the Fifties, few years after David Ben-Gurion read the Declaration of Independence. A histrionic photographer, he took his brothers and sisters, his aspirations and his risky projects and moved from Bagdad to a small Israeli settlement in the desert, since the Iraqi government had reacted quite badly to the birth of its new non-Arab neighbour.

Out of sheer talent for business, he started a photo shop and began immortalizing wedding ceremonies with growing success. His own first name became the new family surname, its brand, and, after he and his clan later relocated in Tel Aviv, a synonym of photography all around Israel. Even though the movie’s focus is on the relationship between the proud artist and his relatives, few doubts arise at the end of the screening. Given the region’s complex and unstable political situation, what if Farag Peri hadn’t left Iraq? Would the Jewish Farag clan have still been able to achieve fame and wealth and keep photographing smiling brides and mustached grooms under the merciless rule of the Arif brothers or of the Ba’ath Party?

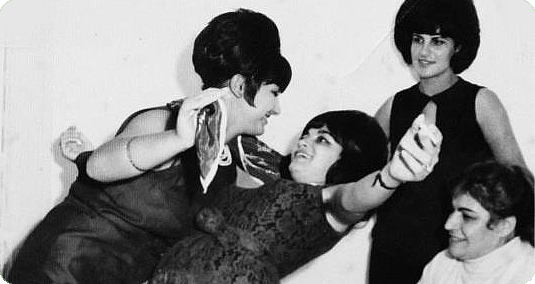

More touching are the stories of solitude and hardships recalled by seven ladies – seven talking heads – in Dimona Twist. After having reached Haifa by ship early in their youth, they were sent to occupy a distant development town called Dimona, halfway between Beersheba and the Dead Sea. Conceived as a pioneers’ outpost in 1953, this desolate strip of desert was settled only a couple of years later, primarily by the poorest among the Sephardic immigrants.

The seven women chosen by Aviad (who dedicated the movie to the late Ronit Elkabetz) are of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic ancestry, born and grown up in Poland or in big modern cities in the former French colonies of Northern Africa – where at the time, as they quietly emphasize, “things were getting difficult for Jews”. Their memories cross decades of economic development and social changes, and skip from the initial problems of integration in improvised schools as young country builders to their daily struggles as toughened adults.

Moving from the crowded boulevards of Algiers and Tunis to the sand of the Negev desert was a shock that left deep marks, that changed forever their approach to life, to tradition and to their own cultural background. But, again, what would have been the alternative for those girls, now women full of humor and dignity, and for their families?

There is no clear and definite answer to all these questions, whether on or off screen. But in the archival materials, in the footage and in the old photos used by Alalu, Farag and Aviad it is possible to find a thin red thread made of naivety, missed opportunities, broken dreams, courage and vague hopes that, in a strange and unsettling way, links the past to the present.

Life is never easy, even in a promised land.