A Life Between Sirens

A heartfelt conversation with a nurse on compassion and resilience through war and pandemic.

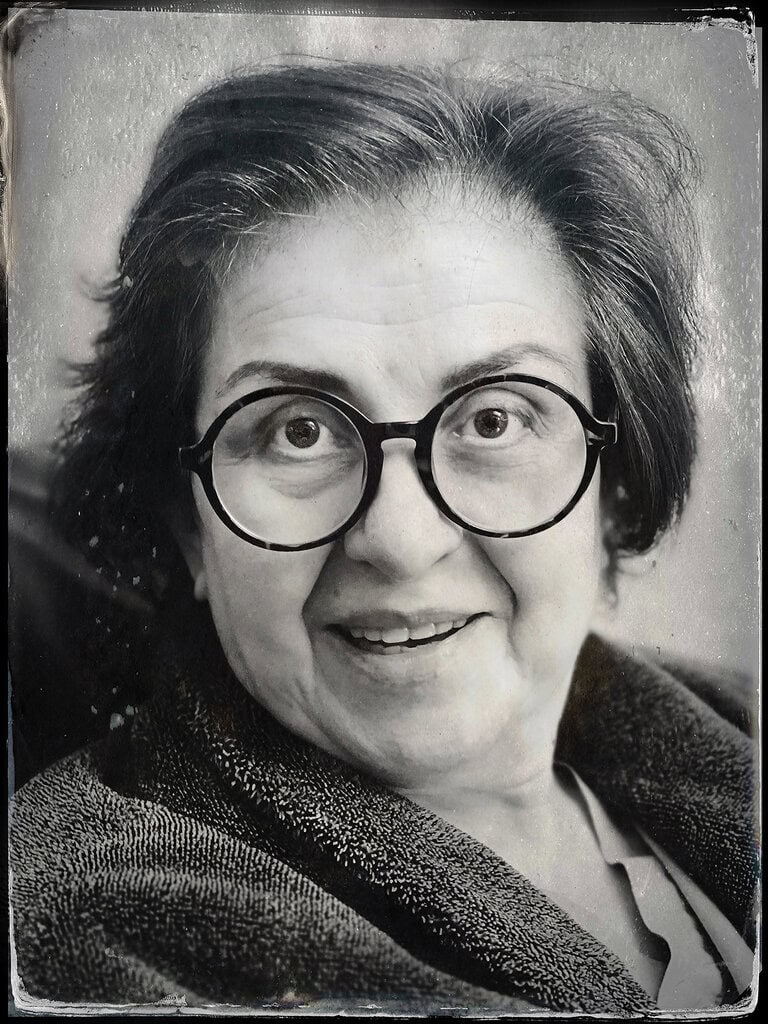

Mina Rahimi – Toronto | I finally arrived at Coxwell Station. The air was surprisingly cool for the season, crisp enough to stretch a moment of quiet into a five-minute walk toward Michael Garron Hospital. I needed that space to clear my head, to line up my questions. It had been twelve days since the war between Iran and Israel began. The woman I was about to meet was Iranian-Canadian. A nurse with more than forty years of experience. A witness to two wars, a survivor of one migration, and a woman who never stopped pushing the boundaries of her own potential.

For more than four decades, Behnaz Rahbar has answered the call, not once, but across time, continents, and crises. She began her nursing career in the surgical wards of Tehran during the Iran-Iraq war, treating young soldiers whose bodies carried the weight of a nation’s trauma. Decades later, in Canada, she stood on the frontlines of a different kind of war —the COVID-19 pandemic— masked, exhausted, but unwavering. And now, as missiles once again rain down on her homeland, she finds herself in Toronto, carrying a familiar ache: helplessness, distance, and the quiet fear of losing those she loves.

Inside the hospital, still fresh with the sheen of recent construction, I asked the front desk for Behnaz Rahbar. They directed me to the clinics on the first floor, but the maze of new corridors quickly dissolved my sense of direction. At one intersection, I stopped another hospital worker to ask again. He smiled and said, “Follow the loud laughter —you’ll find her.”

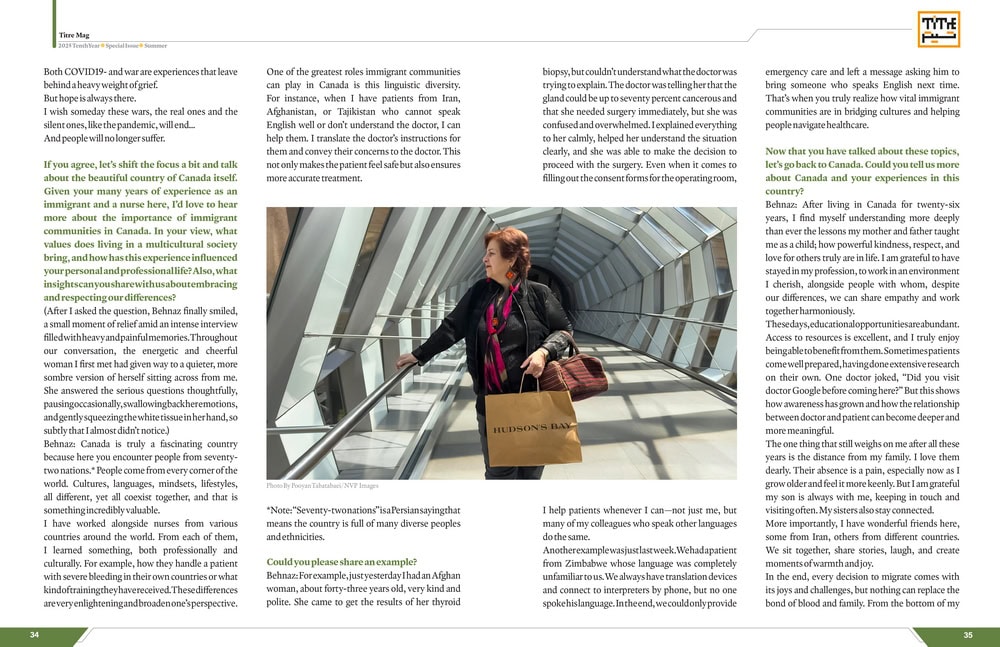

He wasn’t wrong. Near the clinic entrance, I spotted a middle-aged woman with cropped hair, pink running shoes, and bright, stylish glasses. She was weaving between patients, chatting, laughing, fully alive in the rhythm of the work. I turned to the clerk nearby to confirm. She nodded: “That’s Naz. She runs like hell and works like three people. If you want to catch her, you better do it now, before she vanishes into one of the rooms.”

Ten minutes later, we found a quiet spot in the lobby. She handed me a coffee —Tim Hortons, of course— and one for herself. She apologized for the rush with a grin, and just like that, we began our short conversation. “This interview doesn’t look back with nostalgia, it follows a nurse whose life has been shaped by urgency, compassion, and the long echoes of sirens.”

Question: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. I’ll get right to the point: could you tell me a little about your background in nursing, both in Iran and here in Canada?

Behnaz: Hello. I worked in Iran for nearly fifteen years, and now it’s been close to twenty-four years that I’ve been practicing as a nurse in Canada. When I think back to those years, to the time I first started nursing in Iran, I remember the passion and excitement of those days. With such love, with such hope, I went to work. It was wartime then, but despite all the hardships, you felt like you were making a difference. You could help, comfort, and bring healing.

My foundation in nursing was built in Iran. I began at Shohada Tajrish Hospital in the surgical unit. After that, I worked at Shahid Beheshti Hospital, then spent some time at Mehrad Hospital, and finally, I worked at Ali Asghar Children’s Hospital. All those years — all those experiences—shaped the nurse I am today. I learned something from every single nurse and doctor I worked with back then: Dr. Afshar, Dr. Hassantash, and Dr. Elyasian. They laid the groundwork for everything I do now here in Canada.

At its core, nursing is the same everywhere. But the systems, the resources, the structures that support patient care, those are vastly different. Nursing is a profession where learning never stops. Every single day brings a new case, a new challenge, a new lesson. You always have to stay ready, stay curious, stay current. Here in Canada, we have more resources. Training is constant. Everything is more up-to-date, more systematic. But the heart of it remains unchanged: to help, to listen, to care with all your being.

Back in Iran, during those years, there was such warmth among colleagues. It was a deeply human environment. I made lifelong friends, people I’m still in touch with, even now, after so many years apart. Each of them is living somewhere else in the world today, but that connection, those memories, they’re still alive in me.

One thing I have learned over these years is that

Pain is pain everywhere.

Blood is blood everywhere.

Grief is grief everywhere.

But a human is still a human, full of feelings, hope, and the need for care and respect.

And in the end, in both places,

What has always mattered most to me is this:

A person must strive to be human and to act with humanity. Nursing is a profession you have to love. Without love, you can’t last in it. You have to love people. You have to care that someone is in pain, that someone needs help. You must stand up for the rights of the patient, you have to value human beings, otherwise, nursing becomes just a job. And to me, it has never been just a job. It’s a way of life.

Q: From the moment you arrived in Canada, how long did it take before you returned to your nursing profession? And what kinds of jobs did you do in the meantime?

Behnaz: When I first arrived in Canada, naturally it took some time before I could return to my main profession, nursing. The path was long and filled with steps. First, I had to complete a series of exams; without passing them, you’re not allowed to enter the nursing system here.

One of the first things I did was attend an adult high school to earn a Canadian diploma. That credential helped a lot. It made the path forward much smoother. One of the most interesting, and at the same time, most challenging things about working in Canada is that nearly every job —even those unrelated to your field— requires what they call “Canadian work experience.” Before you can step back into your own profession, you have to prove you’re familiar with the workplace culture here.

So, I started writing my résumé. Even though I didn’t have any Canadian job experience, I went out in person and handed it out at major retail stores. One elegant women’s clothing store called Melanie Lyne hired me. It turned out to be a great experience. The manager was incredibly supportive, and I worked alongside colleagues from many different countries in the sales department. If a customer needed help —say, choosing a colour or a style— we were there to guide them. At that time, my English wasn’t fluent, but I gradually adapted to the environment. I still remember how customers eventually began seeking me out for advice. It was a unique and valuable experience.

After that, I sent out more applications and landed a job at a long-term care home. That was my first direct experience in Canada’s healthcare system, caring for the elderly. I received excellent training and learned how differently elder care is structured here, from nutrition planning to daily routines like hygiene, dressing, and medication. I worked there for about a year.

Then I moved to a larger senior care facility while simultaneously preparing for the nursing licensure exam. Here, until you pass that exam, you can’t work as a registered nurse. During that time, I was doing basic caregiving tasks and gaining a great deal of hands-on experience.

Finally, I sat the exam, a five-hour test that was incredibly intense, both mentally and emotionally. Those days were tough, especially the wait for the results. But throughout that entire period, I never stepped away from work. I stayed engaged, kept learning, and pushed forward. And thankfully, I passed the exam on my very first attempt, something that isn’t easy to do.

Question: Let’s go back about 40 years to the time of the war. You were working in Iran during those years. Could you share some memories from that period, and what the atmosphere was like

Behnaz: During those years, in the Iran-Iraq war, I worked in a hospital. It was truly a very, very difficult and painful time. To see so many young people lose their health forever, it’s impossible to put into words. When the wounded arrived in Tehran, they had already been through incredibly hard days. Many came with amputated legs or arms, in intense pain. They were broken, both physically and emotionally, when they reached us. Many had been moved around for days or even weeks in terrible conditions before finally arriving at the hospital.

We worked under the supervision of surgeons who did whatever was necessary. If a limb needed to be amputated, they amputated it. If shrapnel was lodged in someone’s stomach, they removed it. Anything needed to save their lives. But what has stayed with me all these years isn’t just those wounds. It’s the deep silence in their eyes, those looks, the fear, the exhaustion… They all came from the heart of war, carrying a world of unanswered questions.

I’ll never forget the days when they said Tehran was going to be bombed. I was really worried. My son was just a child then, and my whole family was in Tehran. In the middle of that anxiety, I talked to a friend whose father owned one of Tehran’s bus companies called “TBT.” Thanks to their kindness, they managed to arrange a private bus for us. At that time, buses were not easy to find at all. I was truly grateful for the endless generosity of that family.

Very early that morning, I gathered all our relatives and family —anyone who could come, from children to elders— at the South Terminal and sent them off to Mashhad. Watching that bus pull away was one of the most breathless moments of my life. I didn’t know when or if I’d see them again. I packed a small suitcase for myself and went back to the hospital. I stayed there for almost a whole month. We were a group who had sent our families away and stayed behind, ready for whatever might happen.

I only went home once a week to check on the house. Our caretaker, Mr. Amir, was still there. I would ask how he was doing, take care of some house chores, and then return to the hospital. I had told him to call me if anything happened. He had my number and was always attentive.

I remember one day on Zafar Street, very close to our home and even closer to my uncle’s house, a missile hit a house. They brought a young engineer from there to our hospital, but unfortunately, he died from multiple shrapnel wounds. That missile could have struck our house just meters away and destroyed it. I kept one of the large pieces of shrapnel they removed—not out of fear, but as a reminder to never forget what war truly is. I kept asking myself: why so much violence? Why does war make someone lose their hands? Their legs? Their home? Their loved ones?

I always tell myself, as long as we’re here, we must love each other. We must show kindness. We must love. Because war leaves nothing but destruction, just grief, just sorrow, just pain.

Question: Now, let’s move to more recent years. About five years ago, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a different kind of crisis to the world. You were working at a COVID center here in Canada during that time. What do you remember most from that experience?

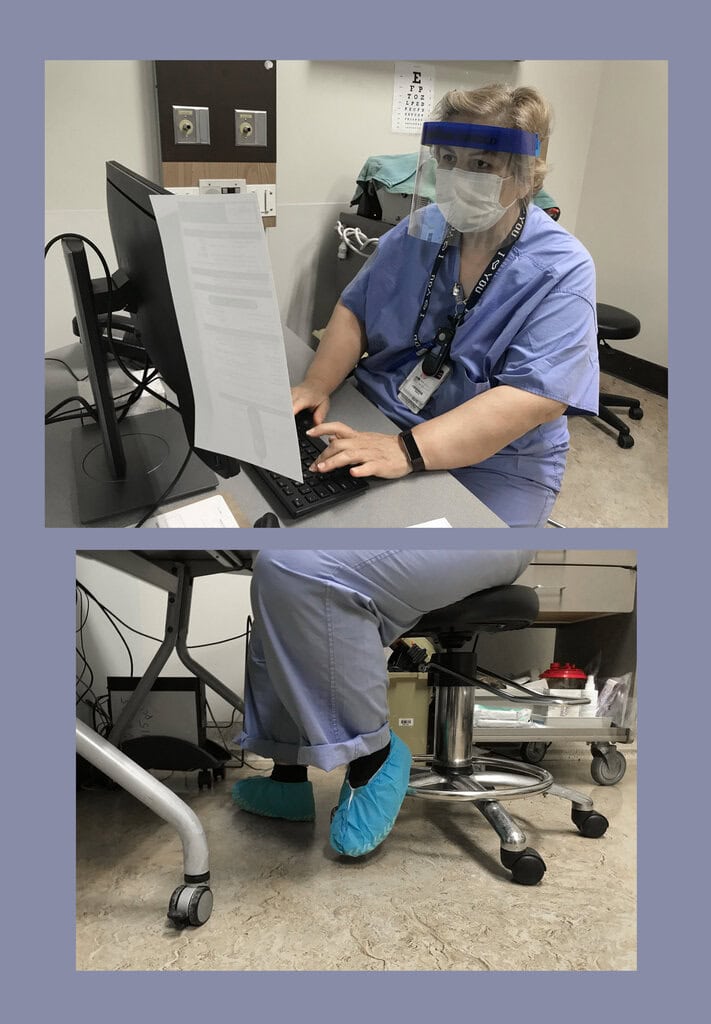

Behnaz: The COVID-19 pandemic in Canada truly felt like a war; a war without weapons, but full of fear and pressure. I was working in the pre-op unit, where we prepared patients for surgery. In those early days, not just us, but the whole world didn’t really know what we were dealing with.

We had to wear full PPE at all times —masks, gloves, face shields, gowns, shoe covers, hairnets— nothing on our body could come in contact with the patients. Even a simple cough or runny nose was a serious alarm. According to the hospital protocol, we had to immediately take a swab and send it for testing. Every tiny symptom was treated with urgency. We worked closely with anesthesiologists who had to assess patients before every operation, especially given the respiratory risks and infection potential.

Later, when mandatory vaccinations were introduced, not everyone agreed. Some nurses refused to take the vaccine and unfortunately had to leave their jobs. But those of us working directly with people’s lives, we had to protect our patients. We had no choice but to be vaccinated.

I myself got very sick twice —body aches, fatigue, headaches— all the symptoms. As we were still in the early stages of the pandemic and information was limited, the protocol was strict: as soon as we showed any symptoms, we had to take a test and go straight home for quarantine. Back then, it took nearly two full days to receive test results, not just an hour like it is now. That happened to me twice.

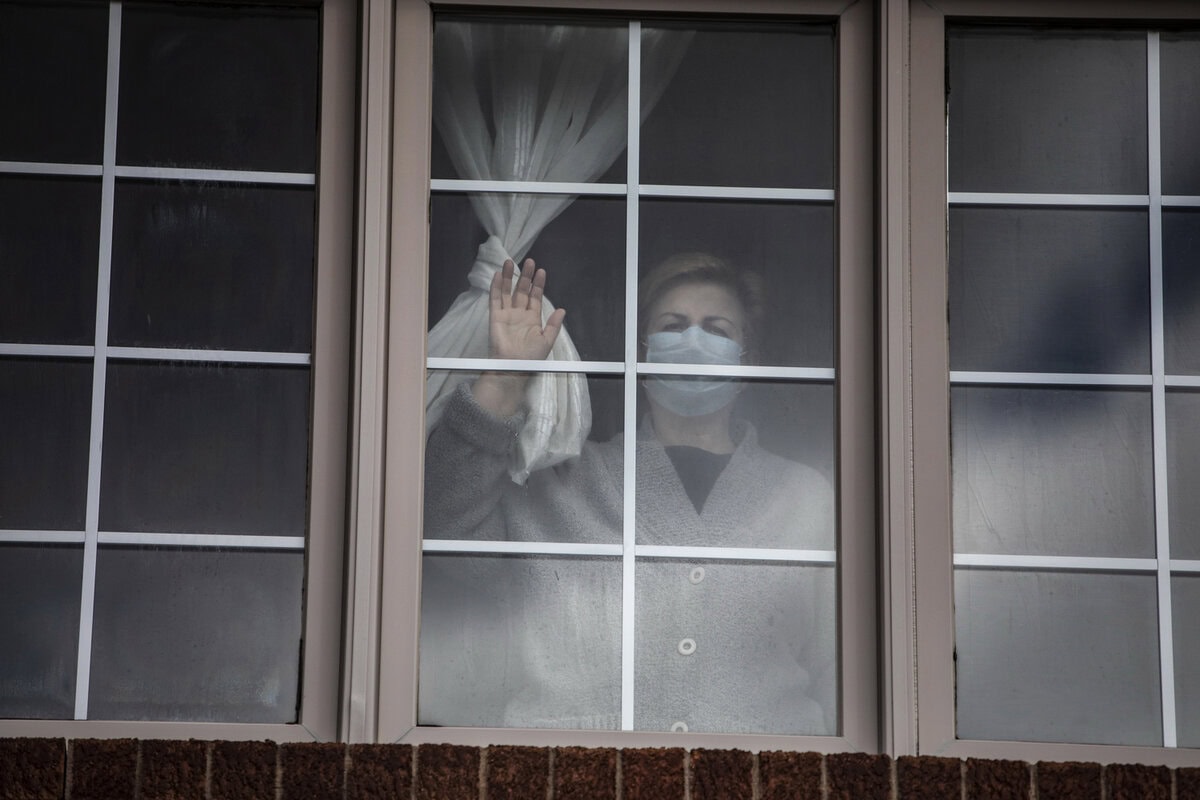

Each time, I spent two full days completely isolated in a room. I wasn’t even allowed to use the shared bathroom. My husband was extremely careful. Everything had to be separated: dishes, the bathroom, physical contact, even hallway distance. And thankfully, both times the test came back negative.

It was a really tough time, not just physically, but emotionally too. You worried about yourself, about your family, and about the patients you’d have to see again soon. We had weekly training sessions. Infectious disease doctors and unit heads would come in to walk us through updated protocols: how to move from one patient to another, how to change PPE, how to sanitize spaces, even how to talk to frightened patients.

Staffing was always short. Nurses kept getting infected or sent into quarantine. The rest of us had to do double the work. And not just us, the cleaning staff, food service, everyone was under pressure. Some days, we could barely breathe from the steam trapped under our masks. You couldn’t even touch your face. One sneeze could shut down an entire unit.

But we supported each other more than ever. There was this strange, deep solidarity between us. No one felt alone. Everyone helped. Every time someone got sick, their absence was truly felt. It was a long and exhausting stretch. Not a single day passed when I didn’t ask myself, “When will this end?”

And now…

Now, when I think about those days, I realize the kind of hell we lived through. Today, we wear masks only in specific cases. That constant anxiety is gone. No more layers of protective clothing, no more fogged-up face shields.

And I think to myself:

What a gift this calm is. What peace we have now.

Those days were a silent world war.

A war with no bullets, but where everyone was wounded, mentally or physically.

And we, the nurses, were the soldiers of that war.

Question: Considering your experiences during the difficult times of war in Iran and the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, I would love to hear from you about the similarities and differences of working in these two situations. In terms of emotional pressure, work challenges, and the environment, what aspects felt the same and what stood out as unique or different to you?

Behnaz: Though working through war and the pandemic were very different experiences, they shared one profound similarity: constant fear and vigilance. During COVID-19, the feeling of war was with me every moment. Truly, the pandemic was a kind of war, a war no one knew where it started, who the enemy was, how it spread, or what to do about it.

It was an unknown force that attacked everybody’s system in different ways, causing illness, disruption, and sometimes death. In war, wounds were physical: pain, blood, and visible injury. But in the pandemic, the enemy was silent. A patient might look healthy but still carry the virus inside.

In war, we worked with passion, love, and despite all the fears, a fiery determination to protect. In the pandemic, that same love was there, but the fear was more psychological, more isolating. The loneliness was heavier.

Yet in both, one had to be prepared, patient, and compassionate. In both, lives were put on the line, whether under falling bombs or an invisible virus no one could trace.

Another crucial difference was that in war, we were physically and emotionally closer. In the pandemic, everything was distant. You couldn’t properly touch the patient, couldn’t smile because your face was hidden behind a mask. Human connection became difficult.

I worked in both times. In both, I witnessed tears, pain, and fear. And in both, I learned that without love for humanity in your work, you cannot endure.

War was war; a devastating conflict where people, willingly or not, were trapped in pain, illness, and loss. And the bitter similarity between the two is their ending…

The place where life no longer exists.

The place where sorrow, death, and silence remain.

Both COVID-19 and war are experiences that leave behind a heavy weight of grief.

But hope is always there.

I wish someday these wars, the real ones and the silent ones, like the pandemic, will end…

And people will no longer suffer.

Question: If you agree, let’s shift the focus a bit and talk about the beautiful country of Canada itself. Given your many years of experience as an immigrant and a nurse here, I’d love to hear more about the importance of immigrant communities in Canada. In your view, what values does living in a multicultural society bring, and how has this experience influenced your personal and professional life? Also, what insights can you share with us about embracing and respecting our differences?

(After I asked the question, Behnaz finally smiled, a small moment of relief amid an intense interview filled with heavy and painful memories. Throughout our conversation, the energetic and cheerful woman I first met had given way to a quieter, more sombre version of herself sitting across from me. She answered the serious questions thoughtfully, pausing occasionally, swallowing back her emotions, and gently squeezing the white tissue in her hand, so subtly that I almost didn’t notice.)

Behnaz: Canada is truly a fascinating country because here you encounter people from seventy-two nations.* People come from every corner of the world. Cultures, languages, mindsets, lifestyles, all different, yet all coexist together, and that is something incredibly valuable.

I have worked alongside nurses from various countries around the world. From each of them, I learned something, both professionally and culturally. For example, how they handle a patient with severe bleeding in their own countries or what kind of training they have received. These differences are very enlightening and broaden one’s perspective.

One of the greatest roles immigrant communities can play in Canada is this linguistic diversity. For instance, when I have patients from Iran, Afghanistan, or Tajikistan who cannot speak English well or don’t understand the doctor, I can help them. I translate the doctor’s instructions for them and convey their concerns to the doctor. This not only makes the patient feel safe but also ensures more accurate treatment.

*Note: “Seventy-two nations” is a Persian saying that means the country is full of many diverse peoples and ethnicities.

Question: Could you please share an example?

Behnaz: For example, just yesterday I had an Afghan woman, about forty-three years old, very kind and polite. She came to get the results of her thyroid biopsy, but couldn’t understand what the doctor was trying to explain. The doctor was telling her that the gland could be up to seventy percent cancerous and that she needed surgery immediately, but she was confused and overwhelmed. I explained everything to her calmly, helped her understand the situation clearly, and she was able to make the decision to proceed with the surgery. Even when it comes to filling out the consent forms for the operating room, I help patients whenever I can—not just me, but many of my colleagues who speak other languages do the same.

Another example was just last week. We had a patient from Zimbabwe whose language was completely unfamiliar to us. We always have translation devices and connect to interpreters by phone, but no one spoke his language. In the end, we could only provide emergency care and left a message asking him to bring someone who speaks English next time. That’s when you truly realize how vital immigrant communities are in bridging cultures and helping people navigate healthcare.

Question: Now that you have talked about these topics, let’s go back to Canada. Could you tell us more about Canada and your experiences in this country?

Behnaz: After living in Canada for twenty-six years, I find myself understanding more deeply than ever the lessons my mother and father taught me as a child; how powerful kindness, respect, and love for others truly are in life. I am grateful to have stayed in my profession, to work in an environment I cherish, alongside people with whom, despite our differences, we can share empathy and work together harmoniously.

These days, educational opportunities are abundant. Access to resources is excellent, and I truly enjoy being able to benefit from them. Sometimes patients come well prepared, having done extensive research on their own. One doctor joked, “Did you visit doctor Google before coming here?” But this shows how awareness has grown and how the relationship between doctor and patient can become deeper and more meaningful.

The one thing that still weighs on me after all these years is the distance from my family. I love them dearly. Their absence is a pain, especially now as I grow older and feel it more keenly. But I am grateful my son is always with me, keeping in touch and visiting often. My sisters also stay connected.

More importantly, I have wonderful friends here, some from Iran, others from different countries. We sit together, share stories, laugh, and create moments of warmth and joy.

In the end, every decision to migrate comes with its joys and challenges, but nothing can replace the bond of blood and family. From the bottom of my heart, all I can say is this: wherever you are, may you find peace, love, and solidarity in your heart, and may you cherish every moment of it.

Question: Thank you for your time. As the last question, during these twelve days of conflict between Israel and Iran, what was the atmosphere and situation like for you in Toronto? What were you doing during this time? How did you follow the news, and how did you stay in touch with your family in Iran?

Behnaz:

During these twelve days of war between Iran and Israel…

I endured some of the hardest days of my life.

How much pain did I carry?

How deeply I worried for all the innocent lives caught in the crossfire?

For those who had no part in this conflict,

Yet found themselves trapped in its merciless grip…

And how I feared for my son,

Pooyan…

My life, my soul, my love.

I worried for my sisters, my nieces,

For my niece’s daughter and her two little ones…

They are the blood and breath of my being.

Without them, I would wither away…

Breathing would lose its meaning without their presence.

Nights without sleep,

Days filled with restless worry.

Endlessly glued to the television, chasing every news update…

As soon as I got home, I would rush through CBC news, then other channels…

Trying to hear what Al Jazeera said, CNN, Iran, America…

Never, not even for a moment, did the news allow us Iranians,

so far away from home,

Any kind of peace.

We were all anxious,

all burdened by fear and sorrow,

Carrying a heavy weight of grief as we went to work.

When we saw each other, we embraced,

Asking with trembling voices:

“What news do you have? Is your husband okay? How is your mother? Your sister? Have they come or gone?”

Everyone—everyone—kept asking about Pooyan.

Dr. Tate called me.

Dr. Eyasi, Dr. Hubbard, Dr. Kwinter…

All worried, asking for updates,

Their voices laced with concern.

Dr. Frecker sent me a message:

“Call. Call Pooyan. He needs to come here. He needs to come back…”

All filled with care, with worry…

No one understands how exhausting and soul-crushing

These constant moves and fears really are…

“For a few seconds, Behnaz falls silent. She curls inward, struggling to hold back a sob. Her voice trembles as she begins again, tears flowing freely, but she refuses to stop:”

I don’t know what to say…

But I know this—so many innocent people,

People so dearly loved,

People who were simply human beings—

all of them,

all innocent—

Have been taken from us by these bombs.

I hope the day will come when Iran—

our homeland—

Finds peace.

And all of us can live again

In happiness and safety.

I love you, Iran.

No matter where I am,

You are always in my heart, in my soul, in my very being.