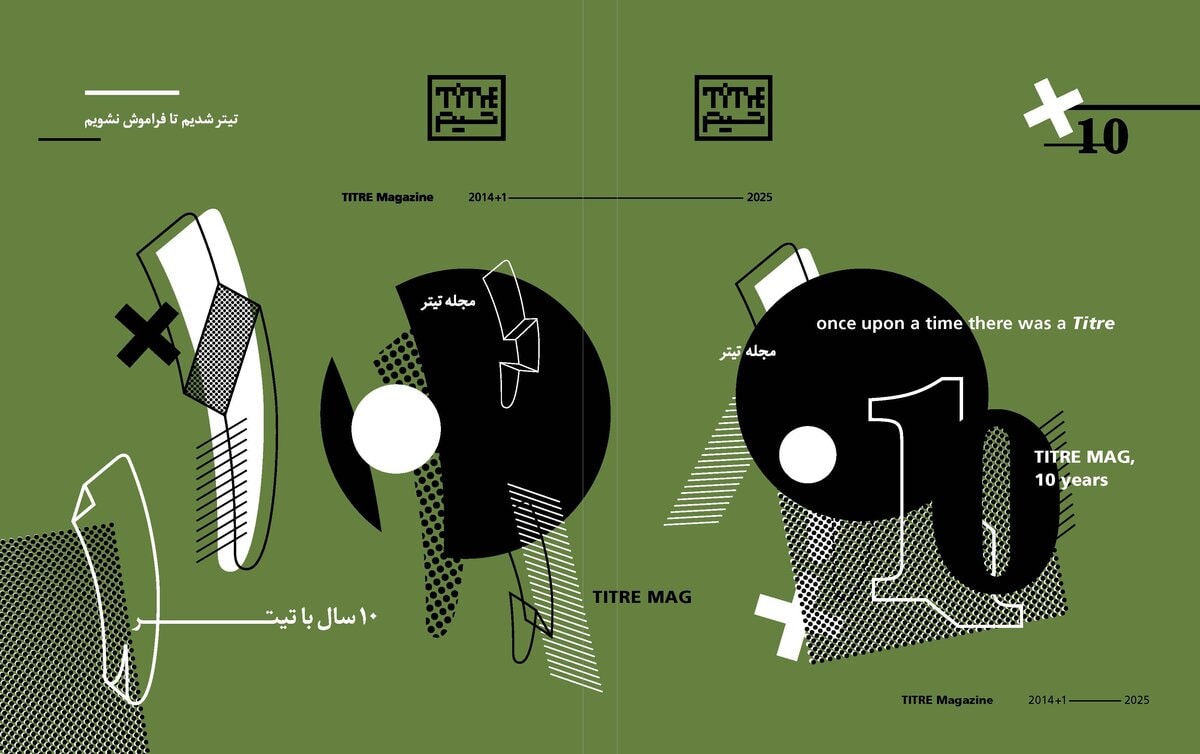

Once Upon a Time, There Was a Titre

10th Anniversary Edition, Opening Editorial, Section 1

Journalist

Canada

Pooyan Tabatabaei

Journalist and Founder of Titre Mag

We Became the Titre So We Would Not Be Forgotten – Part 1

I must have set this piece aside more than ten times. Each time I returned to it, the world around me and the shape of my life had changed. There were joyful days when I smiled at the thought of the magazine’s tenth anniversary, and then there were days clouded with anxiety, war, disconnection, and waves of migrants building a fragmented community. Five months ago, when I first began inviting friends to contribute to this special issue, I had a full celebration mapped out in my head.

I’ve always believed one of our deepest challenges as Iranians is the inability to sustain what we create. That belief carries even more weight for someone like me, an Iranian immigrant in Canada, immersed in the worlds of art and media. So many cultural and artistic projects have fizzled out for simple reasons, and so many publications have vanished before even completing a single year. And yet, here stands this very publication, Titre—the result of shared vision between myself and Helia Ghazi Mirsaeed—still alive after ten years, despite every stone in our path. What could be more rewarding than that?

We compiled a list of artists, journalists, and professionals whose work we’ve proudly hosted over the years. We slowly began reaching out, inviting them to share in our celebration. The work began. In my office, on the whiteboard by the wall, I picked up a red marker and wrote “Editorial” in big letters. Next to it, I drew a red rose, a reminder of how much I had to say. Over the following days, scattered notes on scraps of paper piled up on my desk, waiting to be shaped into a coherent essay once I could see the full structure of the magazine coming together.

On the twenty second day of March 2025, my grandmother—Mama Azar—fell at the age of 85 and fractured her femoral neck. Just as I’ve done so many times over the past seven years, whenever something happened to my grandfather or grandmother, I boarded a plane to Tehran on behalf of all the children and grandchildren. I managed the logistics, her surgery was done, and the intensive care began. Days passed in the hospital and nights at home, and my mind turned to migration, the role of ethnic media in multicultural countries, the responsibilities and contributions of migrants, and dozens of other angles surrounding this complex reality. I scribbled down short reflections now and then, afraid that these scattered thoughts would slip away.

I already had a return flight booked to Canada and a medical procedure of my own scheduled. So I made sure everything was settled for Mama Azar and came back. The operation went well, but the two-week recovery was difficult. As soon as I could, I bought another ticket back to Tehran. My surgeon was not at all happy about me flying so soon, but how could I leave my grandmother alone? Her home is full of the memories of my youth and adolescence, and she herself is a beating heart of love, now living without my grandfather for six years. So once again, I found myself in Tehran, and once again I stood before a whiteboard with my red marker and wrote “Editorial” beside a freshly drawn red rose.

Two months ago, my uncles, worried that something might happen to Mama Azar and that their children—who had not seen her in many years—might miss their chance, decided we should all meet in Turkey on June 21. Ten days before the flight, I had already packed her suitcase. Mine was half-open, lying in the middle of the room. My younger uncle, Shoja, messaged that he and his family had arrived at the hotel and everything was ready. I replied that I had wrapped up affairs in Tehran and that Mama Azar and I would be flying out the following night. My older uncle, Emad, also wrote to say he and his family, along with their new American son-in-law, were on their way to Europe. I let him know I had packed the barberries and pistachios he had asked for. I laid out the last of my things, placed the passport and tickets on the table, and prepared for the trip.

That night, I had worked late, and my eyes had just started to close when a loud sound startled me. I thought it might be thunder. I tried to sleep, but the sound came again. And again. The sky was clear. I got out of bed, pulled off my sleep mask, and walked to the window. It was still dark. My phone rang. Then a stream of messages arrived. Friends were worried—there had been explosions near Parchin, in northeast Tehran. I looked out from the 19th floor where I had a clear view of the area. Nothing visible. Another message. I opened the messaging apps. Something was happening. One report after another began to pour in. Within less than an hour, it became clear—Israel had attacked Iran.

Before dawn, messages flooded in: “Are you safe?” I was confused at first. Then I realized one of the buildings in western Tehran that had been hit by drones looked a lot like ours. That was why people were worried. The war had begun. Tehran grew quieter by the hour. Flights were cancelled. My entire family was in Turkey, sitting by the hotel pool, asking about us whenever they could get internet access, checking the news, and raising a glass now and then to calm their nerves.

I was thrown back to my first year in Canada. My whole family had gone to the United States to visit my uncle, and I had planned to join them from Toronto. I had not seen that uncle in 19 years, and my other uncle who lived in Sweden for 14. Then came the September 11 attacks. My visit to the US embassy lasted less than ten minutes. The officer looked at my Iranian passport, laughed, asked about the weather, and said Iranians were banned from entering the US for six months. My visa was denied. Now, 24 years later, it was missiles and bombs preventing another family reunion.

Left with no other option, I arranged for Mama Azar—now well recovered from her surgery—to stay at a friend’s villa in Qazvin while I remained in Tehran to witness and document the unfolding events. The internet was more unstable than ever, making communication inside and outside the country difficult. My family in Canada was deeply worried and kept urging me to leave Tehran. Memories came rushing back, childhood under bombardment, forced trips to safer cities, then the expansion of Saddam’s attacks. And now, it was all repeating itself, only on a much larger scale.

Most of my days are spent between my writing desk, the balcony where I watch the explosions, and the endless news cycle on Al Jazeera and CNN. Little by little, contributions from friends for the magazine’s tenth anniversary began to arrive. But none of them feel like celebrations. They smell more of longing, sorrow, faded memories of war, and sometimes, faint traces of blood. I write each piece and its author’s name on the whiteboard. Every time I glance at that word—“Editorial”—it lands on my head like a hammer. The red rose next to it, once meant to symbolize a joyous occasion, now carries a very different meaning.

In Flanders fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

July 16, 2025