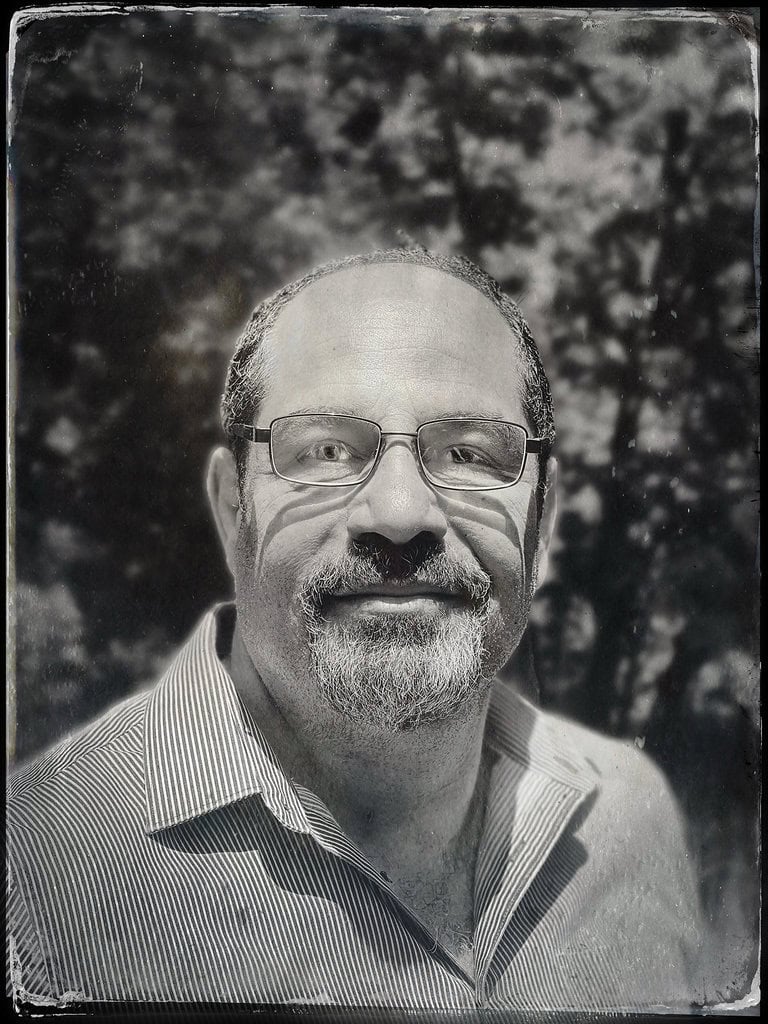

Farhad Ahi – Toronto | You’ve probably heard that art speaks a language without borders—a language infinite in reach and understood by people everywhere. This truth shines brightest in the art of migrants, especially in societies rich with diverse immigrant voices. Countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia have built the foundations of their film industries on the shoulders of immigrants.

When we see filmmakers like Inarritu, Linklater, Del Toro, Bong Joon-ho, Sorrentino, Benigni, Ken Loach, Kiarostami, Kurosawa, and Asghar Farhadi all honored at the Oscars—and their stories understood by people from every culture—it becomes clear that cinema truly transcends borders.

But that does not mean making films as an immigrant is easy. On the contrary, it is far harder. When you are in your homeland, you know the customs and tools of your craft intimately. The unknown elements are so few that you can almost ignore them. But in migration, the unknown is everything. You have to rediscover each piece, redraw your playground, build from scratch, and learn through trial and error, errors that could mean complete failure. This is the price every filmmaker pays, whether celebrated or forgotten. Yet much of today’s vibrant global cinema owes its vitality to immigrant artists who courageously expose wounds that those who never migrated carefully hide.

Nearly two decades have passed since I immigrated to Canada. During this time, I’ve tried—sometimes successfully, sometimes not—to live alongside daily life with cinema and art. Truth be told, it has been far harder than life before migration. This is true for all artists, especially those whose entire lives have been devoted to art. For almost three decades, everything I did was directly or indirectly related to film and television: design, screenwriting, and directing. Even when I worked on exhibitions, they were inspired by cinema.

But life in migration is different. Routine slowly takes the place of creativity, and over time, the mind dulls. The deep analysis fades, replaced by a mechanical need to survive daily tasks. When you spend at least eight hours a day managing mundane things—organizing meetings, preparing presentations—it is tough to find even a few hours left in the day to focus on writing stories or screenplays. Ideas you once drew directly from your community and experiences shrink into simplistic outlines. Everything stays on the surface, not because there is nothing beneath, but because you lack the time and space to explore it.

My old habit was to dive deep, researching extensively, wandering around topics until characters came to life from the wandering. But in this new life, that rarely happens. Still, I try to keep myself updated and continue my creative work as much as possible.

The first couple of months after migration were extremely strange. Back then, in Iran, the film industry’s rhythm was unique: from early January, no new contracts were signed, and producers rushed to get films ready for the festival. The Fajr Festival was always an exam night—films made just in time. After it ended, we raced to collect delayed payments from producers who usually tried to avoid paying. Finally, a couple of days before Nowruz, we’d accept that nothing more could be done and take our holidays.

Even during the holidays, work lingered in our minds, sometimes writing, sometimes designing, sometimes meetings. After Sizdah Bedar, work remained inconsistent because mid-June holidays blocked new contracts. The real working year restarted after that and raced up to early January again. My migration landed in the middle of this cycle, on March 1st, 2009.

Do you remember the morning when Bashu pulled back the tarp on the back of a truck after a long, scary journey? What did he see? An endless green road and a profound silence that aches the ears. A lone cyclist heading toward the horizon. That silence and stillness are indescribable; you have to experience it. That lone cyclist multiplied the feeling of peace and security a thousandfold. That was exactly what I felt on my first morning here. I woke up to the weight of silence. It was as if my eardrums had flipped, trying to purge decades of noise all at once.

On the other hand, I was completely idle, something I had never experienced before. Whenever a project ended, I had several others in early stages to jump to. But now, I had nothing. I did not know what would come next. It was not like today, where fast internet and endless communication tools exist. The first iPhone had just arrived, and phones were still old Nokias without email. Yahoo and Google were barely a few years old, let alone Instagram or WhatsApp.

At first, besides language classes and occasionally working on film concepts as before, I had nothing. My confidence was low; I didn’t apply for jobs yet, everything was new. During this time, after language classes and picking up my daughter from school, I rode my bike with headphones, listening to simple audiobooks tailored to my English level. One day, while riding home, I bumped into an old filmmaking friend in front of the café near my apartment, a surprise meeting.

We had known each other for more than twenty years. He had migrated to Canada a few years before me but had returned to Iran to make films, something I had no idea about. Our subsequent meetings pulled me back into the world of cinema. He wanted to make a film in Toronto and was searching for collaborators and actors. He had a concept but had not finished the script. Our conversations helped him improve his project. I shared my film idea with him.

My friend had an elderly Canadian friend who had previously made and sold a film successfully. We invited him to a meeting. Despite my broken English, we explained our projects. His ideas were more artistic, but he liked my idea more, it had commercial potential. This encouraged me to focus on writing my screenplay, and within a couple of months, I completed a first draft.

I had no other work, and my savings were rapidly disappearing. My English improved, so I began applying for set design jobs. I had a few promising interviews, but none led to collaborations. Meanwhile, I saw an ad in a Toronto Iranian magazine: a film group was looking for actors and crew. I didn’t know it was an Iranian group but sent an email requesting a meeting.

Half an hour later, the director called me personally. He was as surprised as I was. I had known him for years, and we had almost worked together before. He was preparing to make a film called Weightless Weights, a philosophical story about tolerance and justice. The script was finished, and pre-production had begun. I gladly joined the team, which included other old friends. Less than a year after my migration, I was back doing what I loved. What could be better than that?

Weightless Weights became my first real project in Canada. It was an invaluable experience and brought many new friends and colleagues, some of whom became my closest friends here. I felt lucky to have this opportunity. Probably great filmmakers like Sohrab Shahid Saless, Parviz Sayyad, and Amir Naderi never had this chance. I wanted to prove that filmmakers abroad do not necessarily perish. I was young enough not to let caution kill my courage.

Weightless Weights broadened my knowledge of Toronto’s independent filmmaking scene and changed my perspective. The fact that making films here did not require endless bureaucratic permits and censorship was invaluable. I wanted to repeat this experience and share it with others. When my friend returned to Canada for a painting and photography exhibition, I visited him. He had registered a Canadian company and wanted to make his first film here. He had a ready concept, and I had a screenplay in search of funding. We were joined by Yadi Shahbazi, a cinematographer friend, and the three of us formed a film production and education company with a film club.

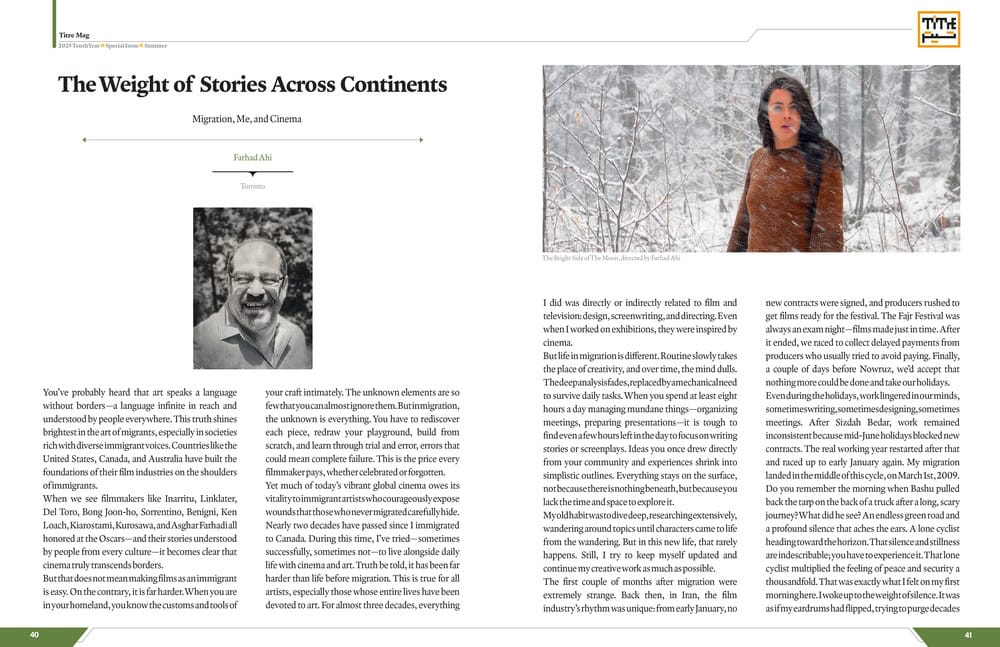

Our goal was to make the first few films ourselves, then scout younger talents from our film school, entrust them with directing, and afterward take roles as producers, sometimes writers, production designers, or cinematographers. Our first production was my screenplay, The Bright Side of the Moon. Then we planned my friend’s film Toronto Seven in the Morning. Unlike the action-packed film our elderly Canadian friend expected, it was a mix of drama and thriller, which made it challenging. Another challenge was shooting in the harsh Canadian winter deep in the forest with a very limited budget, an inexperienced crew, and amateur actors.

Despite all difficulties, inexperience, and financial constraints, the film was completed with dignity. It had a limited release in Toronto, and even the Superchannel cable network bought it. It was accepted in a couple of festivals, gaining some respect. However, the film’s income was not enough to immediately launch my friend’s project. So he returned to Iran again, this time for a longer stay. The production company eventually became economically unviable, and we all had to take day jobs. The closure was a huge blow to our artistic momentum but did not break our filmmaking spirit.

We kept trying to make films and attract funding, occasionally coming close to success, but external forces always interfered. From Trump’s arrival in 2016 to Toronto’s mayoral change in 2017, every shift disrupted our progress. During this time, I served on the jury for the Eastern Breeze Festival in Toronto, which featured a short and mid-length film section. This connected me with a fascinating collection of contemporary Iranian short films.

Cultural and cinematic events, specialized gatherings, and film clubs inspired by ours helped us stay connected to Toronto’s filmmaking scene. The Two Weeks with Iranian Art festival soon became independent and was renamed the Nasim-e Sharghi International Festival, showcasing films from Iran and other Eastern cultures. This festival was one of the most significant factors in sustaining our artistic continuity.

Seeing films from all over the world was a rare and precious opportunity that only such festivals can provide. My active involvement led me back into filmmaking after a four-year break, this time writing and producing short films. The return was more mature and conscious and resulted in two award-winning shorts recognized at prestigious international festivals. This journey continues, and after over three decades in film, cinema, and television, I remain as passionate as I was on my first day at Baghe Ferdows Film School, eager to tell stories through images.