Journalist

Canada

Pooyan Tabatabaei, Toronto | As Canadians welcomed the arrival of 2026 with family gatherings and quiet celebrations, a very different reality was unfolding thousands of kilometers away. In Iran, the new year began amid widening unrest. For the Iranian Canadian community, the first days of January brought not only concern but a creeping sense of dread. Phone calls that once connected Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Calgary to Tehran, Rasht, Isfahan, Shiraz, and countless smaller cities began to fail. Messages stopped delivering. Video calls froze and disappeared. Within days, many families lost all direct contact with loved ones inside Iran.

What began as anxiety quickly hardened into collective stress. Community organizations, newsrooms, and informal family networks were flooded with the same question repeated over and over. Does anyone know what is happening on the ground. As reports of violence began to circulate through fragments of information and diaspora media, worry shifted into frustration, then sadness, then anger. Parents feared for children. Children feared for parents. Many Iranians abroad remain unable, weeks later, to confirm the safety of relatives and friends.

By early January, protests that had carried over from late December were spreading rapidly. Reporting from international outlets, human rights groups, and Iranian sources outside the country pointed to demonstrations driven by a mix of economic pressure, political grievances, and long-standing public anger. Tehran was repeatedly cited as an early focal point, with closures and protests in and around the Grand Bazaar carrying symbolic weight because of its historical role in moments of national upheaval. From there, unrest expanded across multiple provinces and cities, including Rasht, Isfahan, Shiraz, Kermanshah, and surrounding urban areas.

The decisive turning point came in the first week of January when Iranian authorities imposed sweeping restrictions on internet access and telecommunications. By January 8, multiple international monitoring groups described the situation as a near total nationwide blackout. Ordinary citizens were cut off from global platforms and often from each other. Journalists inside the country were effectively silenced. Families abroad were left relying on secondhand reports, delayed voice messages, and occasional brief calls routed through unstable connections.

This blackout shaped everything that followed. Casualty figures became deeply contested, not only because of political narratives but because independent verification was largely impossible. Iranian state authorities later released an official death toll of just over three thousand people, stating that 3,117 individuals had been killed during the unrest, including civilians and members of the security forces. At the same time, unofficial and independent channels reported vastly higher numbers, with aggregated estimates from human rights groups and independent media placing the death toll as high as forty thousand, a figure authorities strongly rejected and which remains impossible to independently verify under current conditions.

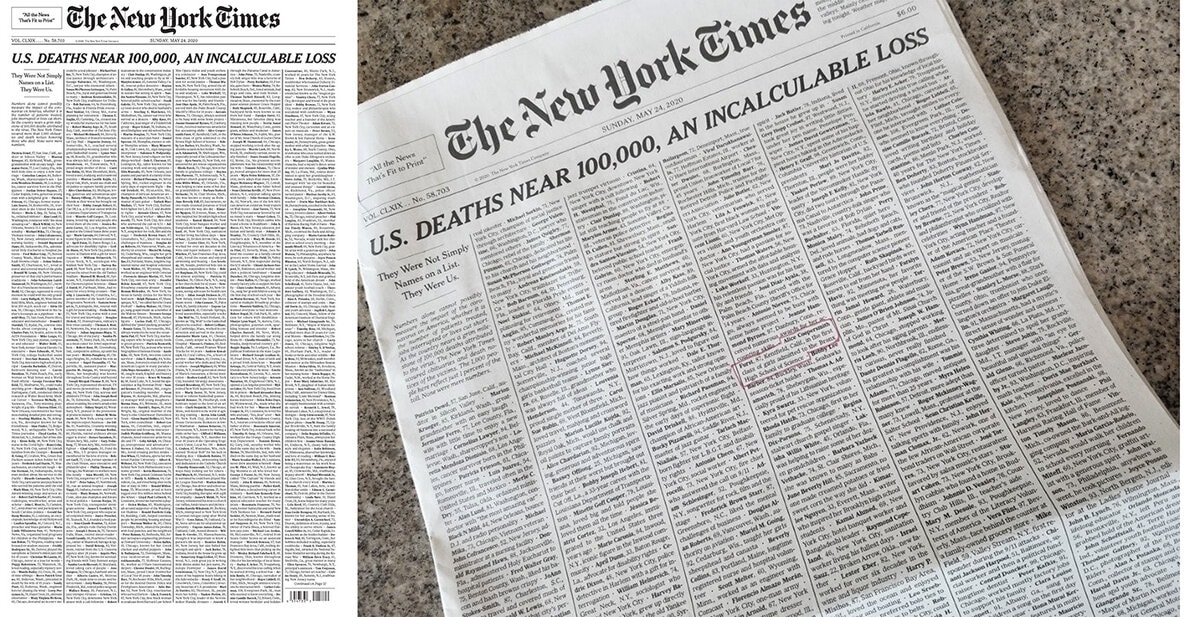

In early February, the Iranian government took the unusual step of publishing a list of names of those it identified as victims. On February 1 and 2, 2026, an official list was released containing the names of 2,986 individuals, with additional cases still under review. In a striking moment of state media coordination, three Iranian newspapers, Sazandegi, Payam-e Ma, and Iran, published the full list of names on their front pages instead of conventional headlines, a move widely compared by observers to the New York Times front page memorializing COVID-19 victims.

Injuries remain even harder to quantify. Independent estimates suggest that the number of wounded may be many times higher than the number of deaths, potentially reaching into the hundreds of thousands nationwide. Iranian authorities have not released comprehensive injury statistics, and hospitals and medical staff were reportedly under pressure to limit information sharing. Human rights groups warned that many injured protesters avoided hospitals altogether for fear of arrest.

Alongside reports of deaths and injuries came accounts of mass arrests. International organizations described large scale detention campaigns following the peak days of unrest, warning that detainees faced a serious risk of torture and ill treatment. Funerals and mourning ceremonies for those killed became flashpoints themselves, at times turning into new protests.

Within this broader national picture, bazaars appeared repeatedly as symbolic and physical sites of confrontation. The Tehran Grand Bazaar was widely referenced in early reporting as an initial catalyst. In Rasht, reporting later focused on a deadly incident around the bazaar area during the height of the crackdown. In western Tehran, a major fire at a market in Jannat Abad in early February drew intense attention and speculation. These incidents are mentioned here only in outline, as each has its own complex timeline and competing accounts that merit separate, detailed examination.

International reaction unfolded in parallel. The United Nations human rights system issued statements condemning the use of lethal force against protesters and calling for the immediate restoration of internet access. The European Union moved forward with new sanctions related to the crackdown. Canada joined allied countries in public statements expressing alarm at the scale of violence and arbitrary arrests. Iranian officials, for their part, rejected outside criticism and framed the unrest as the result of foreign interference and misinformation.

At the same time, the regional and global security environment added another layer of tension. In January, the United States increased its military posture in parts of the Middle East, citing the need to protect personnel and deter escalation amid growing instability. Separately, unverified reports circulated widely in diaspora media and among analysts suggesting that Chinese and Russian heavy transport aircraft had landed in Iran. These reports were often accompanied by speculation that the flights were carrying military or security related equipment. No independent confirmation has established the nature of any cargo, and neither Beijing nor Moscow has publicly detailed the purpose of such movements. Nonetheless, the reports fed a perception among many Iranians that the state was preparing for prolonged internal and external pressure.

Cultural figures also responded. Iranian artists, filmmakers, and writers inside and outside the country issued statements condemning violence and mourning the dead. Musicians and artists internationally used concerts and public platforms to draw attention to events in Iran, while those in exile spoke openly about the psychological toll of watching events unfold through silence and fragments.

As of three days ago, the situation remains unresolved. Street protests have largely subsided in recent weeks, with the last widely reported demonstrations occurring around Saturday, January 11, but reports of arrests, trials, and ongoing repression continue to emerge. Internet access has partially returned in limited areas over the past ten days, yet the country as a whole still does not have normal or unrestricted access to global networks. Communications remain restricted, and many families abroad still have not re established reliable contact with loved ones.

At the diplomatic level, talks have reportedly begun in Muscat between Iranian representatives and foreign interlocutors. These discussions are described by officials as exploratory, and their outcome remains uncertain.

For the Iranian Canadian community, the past weeks have been defined by waiting. Waiting for messages that do not arrive. Waiting for confirmation that someone is alive. Waiting for clarity in a fog of conflicting numbers and incomplete facts. What is clear is that the combination of violence, mass casualties, and information blackout has left deep scars, not only inside Iran but far beyond its borders.